Multi-Scale System Perspective of Social Tech and The State

Connect to Check | 3

The goal of this article series is to examine the connection between social technology and the state. Having added substance to the states of our world, and having already unpacked the hyper-connective and hyper-social accelerant that social technology (s.tech) is becoming, moving forward it would help to think about how global spaces, including the states and the citizens within, are organised.

Panarchies, Disks and Circular Arrows

There is no one-size fits all. Looking at twenty-first century societies requires an adjustable scale. Luckily for us, as outlined by global risk and response systems-wizard Daniel Smachtenburger, there is a particular framework for viewing societal spaces. Structure is a guiding principle within the Structural Layers Model (SLM)1:

Infra-structure

Social-structure

Super-structure

With the concepts of structure and movement inherently linked,2 a good place to begin thinking about the relationship between each layer of the SLM is grasping how they move (thus change) over time. In terms of dynamism, then, we can start by saying the relationship between the three SLM layers is multi-directional:

Infra-structure ↔ Social-structure ↔ Super-structure

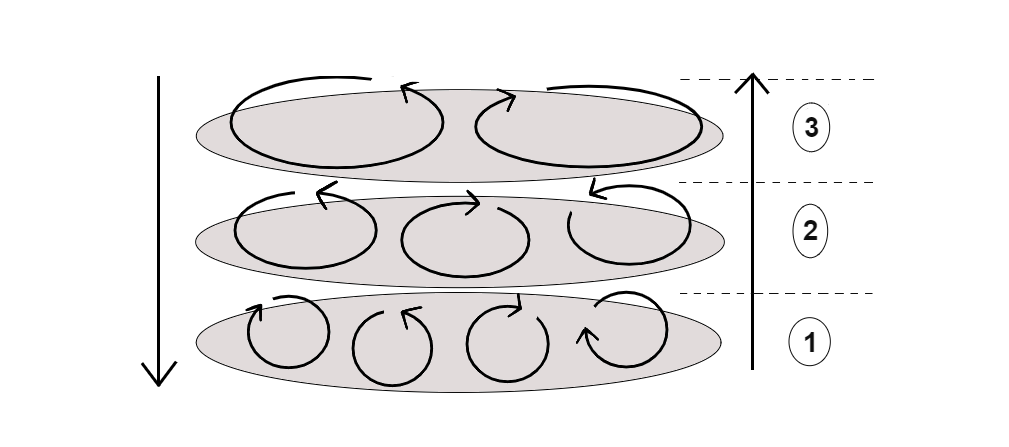

Now we have pinned down a rough directionality, adding further scaffolding to the model in progress, imagine these moving layers as “stacked” one upon the other. This allows us to orientate ourselves, top-bottom/ bottom-top.

What appears in my mind is a structure somewhat akin to a “panarchy”. In fact, if a child was to draw it, this panarchy-esque structure may look something like:

Pan is the classical Greek God of nature and the wild. Panarchy Theory, developed by Gunderson and Holling in the late 1990s, describes adaptive cycles in complex systems, emphasising emergent resilience, interconnectedness, and transformation across varying scales. Integrating ecological, economic, and social systems, Panarchy Theory has morphed into a framework for thinking about how systems across these domains grow, collapse, and reorganise. Convergence, so the Panarchists say, helps understand the elusive phenomenon of emergence. Through multi-scale feedback processes innovation and sustainability are supposedly fostered across a panarchy, suggesting an adaptive and complex mechanism beneath.

To begin systematising the imagined panarchical model above within the framework of the SLM to create the “SLM Panarchy”, notice how the individual layers (the stacked “disks”) each feature separate subsystems (circular arrows).3 Like an old-school stack of CDs, each disk contains a multitude of information, commands, and potential actions. Like an individual disk, each file on the CD, each subsystem within the entire structure, can tell you a lot on its own, but when viewed in the context of the “whole” can express more so still.

But let’s stop talking about panarchies, disks and circular arrows for a second. Anyhow, do these things even relate to the state-based organisation of habited spaces around the world? Well, I think it was Thomas Edison who once said, “To invent, you need a good imagination, and a pile of junk.” We certainly have our “pile of junk”. Now for the “imagination” part.

Driving Fast

To drive you need a vehicle, fuel, and a direction to head in.4 Panarchy Theory provides a framework for understanding how multi-scaled systems embedded within other systems operate across space and time. The structure provided by panarchy guides our movement from system to system, from layer to layer. Vehicle and fuel, check.

Smachtenburger’s SLM, on the other hand, helps to think about the organisation of people within a given space. Specifically, as the name suggests, SLM focuses on the various structures (both physical and metaphorical) that are built to support human organisation across varying scales (e.g. a village to a township to a megalopolis). Direction, check.

The combined SLM Panarchy becomes a way of peering under the hood of various global subspaces, putting us into a better position to grasp the underlying mechanics when it comes to the organisation of people, governance and s.tech within a given state system. How they interrelate and interact will be the focus from here on out.

Layer-to-Layer

Turning our attention back to movement, imagine Layer 1 of the SLM Panarchy as composed of smaller, faster moving subsystems. Because this is the structural layer closest to the everyday people that inhabit these state spaces, there are both more subsystems at this lower level and the subsystems themselves experience higher “turn-over” (entropy) rates than the levels above.

In other words: there is less time between these subsystems coming into and out of existence.

Conversely, the upper layer of the SLM Panarchy, - in this instance, Layer 3 - contains the slowest moving subsystems with the longest thus slowest rates of entropy.

Being causally multi-directional, each subsystem, irrespective of layer, can affect (most often through second, third etc order effects) another subsystem in another layer. In our example, we can imagine how Layer 1 (Infra-structure) can influence Layer 2 (Social-structure), and Layer 2 (Social-structure) can influence both Layer 1 (Infra-structure) and Layer 3 (Super-structure). (This will make more sense shortly, promise.) Generally, the Social-structure acts as a buffer between the top and the bottom of the state space.5 Whilst there are many cases where top can influence bottom, only some cases exist where the bottom directly influences the top. (We are getting to it, I swear.) Whilst rare, these edge cases are very interesting to observe.

As for making sense of it all: the bottom layer: infra-structure (i.structure), literally refers to the “infrastructure” (in a built environment sense) that is all around us, at any given point in space and time. Look around you. What do you see? An apartment? A street-lamp? An office building? Being the layer physically closest to us, basic everyday organisational structures that we take for granted, things like roads, healthcare, education and administrative, public works systems, are all included in this lower structural landscape.

Slower components do exist within i.structure (e.g. large-scale renewable energy projects) but the vast majority of Layer 1 is very frenetic, fueled in large part by the everyday hyper-novelty that characterises both our species and the turn of the century. Permitting myself a moment of philosophising, perhaps, because our individual timeline is not that long (i.e. around 70-80 years), the structural layer physically closest to us also involves many fast moving components that are highly entropic because the subsystems and components within i.structure are a direct, often physical extension of us. In a microcosm, we humans are highly frenetic. Intuitively, the systems closest to us would be too.

Also emerging in Layer 1, through both the physical and digital space, our individual “tech-stack” encompasses use and interaction with technology on a personal level. Whilst this includes physical objects that host access to the digital space, like smartphones, Wifi routers and laptops, our tech-stack also includes digital objects6 such as the internet and public databases.

Through the combinations of digital and physical objects like 5G networks and blockchain, faster communication, real-time sharing, and contract-signing, is enabled both locally and globally. All of this occurs through the i.structure layer. If we imagine the combined SLM Panarchy as a biological system like a plant, i.structure would be the root system that supports growth throughout the rest of the organism. Roots, in this sense, function as the most basic system of passing information up and down the overall system. Information is a key component of s.tech. We saw how it is also a key component of state control. Just putting the two and two together.

Information Flows

In the middle layer we have social-structure (s.structure). Brushing aside, for now, the obvious relation to newly emerging phenomena like hyper-sociability mentioned in the previous articles, SLM Panarchy’s Layer 2 is fabricated largely from the “legal agreement field” that runs throughout societies and geographic locations.

Back to our car analogy, for a direction to be followed, a map, mental or physical, is required. Agreement fields can be mapped, at least to some varying degree of accuracy, by observing the flow of information. We used to draw maps. Now we have different forms of media to guide us. Information, in the twenty-first century, passes through a media of some kind. According to the Pew Research Centre, 54% of American adults get their news from social media, and around 77% of global respondents did too.

Following information flows through the media can tell us a lot about the state space in question. Simple cursory questions include: Are information flows open or closed? How steady is the flow of accurate information top-down compared to bottom-up? If the flow is unsteady, for example, and the information innacurate, then most likely the state space in question is more kleptocratic than if the inverse was true.

Pushing a little further, in a recent empirical analysis of dictatorships, (although there could be some overlap with kleptocratic states to some lesser degree too7) researchers argued that “authoritarian regimes are closed with very limited information flows, but their political leaders also need information to sustain their authoritarian rule”.8 Their analysis suggests the more power that is shared amongst the ruling elite (who are usually connected to the state apparatus in some capacity), the more transparency they require from the media, not because they want freedom of information to their people, but because each political agent wants to keep an eye on their buddy.

Yes “authoritarian leaders strategically use the media to collect information on local officials’ misconduct”.

Of course they use it to monitor their “citizens’ dissatisfaction with [the] regime”.

Why would they not “offer [the] public information with which they can monitor each other’s activities under the power sharing structure”?9

Information is a key component of control and power-maintenance at state-level organisations. Whereas information begins some of its journey in the root system of i.structure, information really takes a solid and cohesive form throughout the s.structural space because this is where, ultimately, is where the first layers of actionable meaning is added.10

Decentralised s.tech, and the emergence of hyper-connectivity and hyper-sociability along with it, provides a means for media, and thus information, to move between the people, not just the authoritarian, kleptocratic, or regular old state, regardless of whether the state or the fourth estate agree with it. The people inhabiting the space a state has carved out for itself, through s.tech, are able to equally carve their own, personal information channel through which a host of raw and deregulated information can flow.

Rules of law and socio-economic cleaving and binding can be contextualised by following such informational flows. The actual content within the s.tech space (what we see and interact with) is largely governed by the behaviors and entropy rates within the s.structure layer, whether or not s.tech is completely controlled by the state (e.g. North Korea’s centralised media) or by the people (e.g. the distributed server system that hosts blockchain across the world).

State institutions and organisations are mostly responsible for upkeep and enforcing these agreement fields between citizens. If the state is ineffective, or overtly cunning, these fields can be maintained or re-aligned by the populace themselves (e.g. independent, self-governing groups like in Liberia or the Amazon territories). Collective action ignited the Arab Spring (2010–2012), and given s.tech's role in mobilisation - a key characteristic of hyper-sociability (see Part 2) - in this case social media platforms bypassed traditional state-controlled media, and the people took it upon themselves to change the localised agreement fields themselves.

S.tech not only branches out at the level of the s.structure, it finds both scale (how many people have effective access to social-mobilising s.tech) and variety (what types of s.tech are available, or can be created and distributed by the state or people). Thus, Layer 2 of the SLM Panarchy becomes not only the stem but also the limbs of our organism. From this branching more people within global subspaces are gaining more access to s.tech, compounding the growth of social limbs everywhere. Such branching is conducive to both hyper-connective11 and hyper-sociability12 conditions.

Final Layer of Meaning

The final layer: superstructure (sup.structure), refers to the deeply ingrained systems of thought, perception and sensemaking13 present amongst the people in a given location.

Sup.structure pretty much “encompasses everything from legal systems and political entities to educational frameworks and media narratives, forming the context within which human agency operates.” If we were to zoom into a certain subspace, there may be nothing more ingrained, nothing more alive, than the emergence of religion and culture. However, while these subsystems are larger and slower than those from the layers below - to the point where they can stagnate and decay over time - they can still respond quickly to stimulus from the lower levels (e.g. the Catholic Church, in particular the Vatican-led attempt at modernisation following contemporary criticism and failures).

Feedback loops are a key feature of Panarchy Theory. Feedback loops also underly the architecture of most social media platforms. Amplifying user engagement through mechanisms like likes, shares, and recommendations, positive loops encourage content creation by rewarding interaction, while negative loops can reinforce biases or spread misinformation. Algorithms prioritize high-engagement content, often creating echo chambers. YouTube's recommendations can influence users’ perspective, while Instagram's likes foster validation-seeking behaviors.

Looking at the proliferation of digital narratives around modern movements like Black Lives Matter is a contemporary case study how s.tech can shape modern interpretations of historical and cultural constructs, influencing collective action intended to make genuine change from within the sup.structure layer. States often have a direct influence on religion and culture in a given area (e.g. mass displacements like the Rohingya and other groups in Myanmar), even causing diaspora dynamics across other local and global subspaces.

If i.structure is the roots and s.structure the stem and the limbs, then sup.structure is the interaction between the entire organism and the surrounding ecosystem. The intimate and unavoidable connections of the two characterises this top layer. Hence, paradoxically, the top of the SLM Panarchy, through various feedback loops, appears as close and influential to the lowest layer, despite being most removed (the ordinary people of the state space are not close to the state-level apparatus, operating alongside religion and culture at the s.structure level).

Constraints are implemented, for the most part, from this super.structural layer.14 From the top, governing bodies, be them political, social, technological, spiritual or simply plain old coercive in nature, often attempt to constrain, or at least in some way manipulate the running of, s.tech. With the Weberian definition of stateness provided earlier,15 the ownership of force in a given territory allows limiting legislations and social media “crack-downs” to occur from this top-down position, because states hold the capacity to enforce whatever that state so wishes. Hence the causal directionality mentioned earlier from Layer 3 to Layer 1, and not the inverse.

Yet remember the central theme of this series is not just stateness, but s.tech also. What effects then, could s.tech and the accompanying hyper-connectivity/sociability phenomena have on the function and operations of both legitimate and illegitimate states across the planet?

This is an arbitrary name, given for the purpose of future clarity, and not the “official” name for the structural worldview outlined by Smachtenburger.

From anatomy (Higgins, 1985; Wakeling et al, 2011) to ecology (Joo et al, 2022), from social movements (Willems & Jegers, 2012; Farine & Chimento, 2024 to music (Sievers et al, 2012).

Both the stack of disks themselves and the smaller subsystems associated with each layer vary in their size and function (input + output, causal directionality etc).

A valid license is also desirable.

“Top” and “Bottom” purely refers to the orientation of layers and systems in the model we are building to understand global state spaces and the movements within and across them. It is not referring to sociological frameworks (e.g. social strata or “elitism”) - they largely remain bound in the Social-structure layer directly.

Objects that exist in the digital space alone (e.g. internet database), as compared to an object that lets you access that database (e.g. a laptop), as compared to an object that sits in the overlap between the digital and the physical (e.g. a wifi router).

Because kleptocratic states tend to fall into disarray and fail, so their use of the media becomes nullified. See the kleptocratic framework put forward by Sarah Chayes in “Thieves of State”.

Ibid.

Actionable Meaning refers to the ability, justification and means to take collective action based on shared meaning (e.g. social movements, egregores, activism).

Both by increasing the density of interconnected nodes and creating complex cause-and-effect chains, amongst other things.

Both by aiding in the global and virtual expansion of social interactions and by increasing frequency and accessibility of social engagement, amongst other things.

Sensemaking in this context refers to the ability to a) interpret the reality around you in the most efficient and accurate way possible to infer correct choicemaking and partake in correct decisionmaking and b) to make as much meaning as possible, whilst maintaining values that result in net-positive outcomes for you and the people around you.

Constraints also stem from the infra-structure layer, but largely because the state-apparatus is failing.

A “state” equates to a group of people with a legitimate (and effective) monopoly of force/violence in a given geographic territory.