Kali Trampling Upon Shiva (See Endnote 1)

Aggression

Richard Wrangham has a lot to say about aggression. An esteemed primatologist and writer of a Top-5 Revelatory book of mine: The Goodness Paradox, Wrangham framed his observations around the evolutionary concept of self-domestication.

Over time, a species domesticates itself for a set of environmental advantages. I know we love to say how we domesticated man's best friend but in reality if those early wolves did not see a benefit in gaining more food, warmth, shelter and added protection they would have never gone near our ancestors, let alone let us pet them and name them Buddy. “There’s a good boy.”

What followed was a litany of evolutionary changes. From floppy ears to less distinction between genders, this process of self-domestication can be seen in mammals across the board, from foxes to elephants. To understand how this process occurs, Wrangham first highlights two categories of aggression:

Reactive

Proactive

Wrangham, a field-based primatologist (literally sitting in the Congolese jungle for months on end), noticed that Bonobo chimpanzee troop-members - particularly male troop members - who showed signs of reactive aggression were targeted, ostracised and in some cases killed by bands of their fellow troopers. Anyone who has studied group-dynamics would not be shocked by this. Person A acts up and Person B, C and D work together to stop Person A from acting up again. However, the very fact that these chimps worked together, planning and confronting the aggressor suggests a utilisation of proactive aggression on their part.

For a more relatable example, think about us: homo-sapiens. Anyone who has ever sat in a car may relate to this one. We are driving down the road and another driver runs a red light, almost crashing into us. Chances are a few of us in the car would express anger (aggression) at this other driver. Shouting, choice words and hand-waving are a few common reactions. Maybe even, in a fit of rage, some of us would get out of the car or chase the perpetrator. Reacting to the situation as and when it is happening - in the now - would be classified as expressing reactive aggression. If you then continue to follow the other car, all the while plotting and scheming with the rest of us about what you are going to do to them once you have caught up to them, that would be proactive aggression. You have planned an act of future aggression. Road rage aside, how do these types of aggression lead to self-domestication?

Wrangham’s Goodness Paradox says that we have been self-domesticating since we began cooperating in groups of hunter-gatherer bands. Members who expressed overly-aggressive characteristics were easy to identify in these smaller, tighter-nit bands. Just like the Bonobo chimpanzees, other group members would plan and execute attacks on these reactive aggressors, using proactive tactics to do so. Over time this means that traits of reactive aggression were selected against (literally forced out of the group) whilst traits of proactive aggression were selected for (because it worked…). This means that in our species, we see on average - when compared to other primates and mammals - less instances of reactive aggression and more instances of proactive aggression. Voilà- self-domestication, here we come.

This seems to suggest that, for group cohesion, proactively taking care of non-conforming group members improves group cohesion over time. Antifragility goes up. But the paradox quickly becomes clear: we are substituting one type of aggression for another. We are bruteforcin’ our way to harmony. It has got us this far, but just how far will it continue to go?

Reading about the Goodness Paradox got me thinking. How good is selecting for proactive types of aggression whilst selecting against those that are reactive? One side of me thinks that, yes, it is pretty bloody good because it stops potential murderers or other general psychotic concerns from really letting loose. It also acts as an effective countermeasure against the lone strongman takeover such as despotic, autocratic or dictatorship-style leadership. It puts power in the hands of the many. But is this all that promoting proactive aggression does for us?

The process of self-domestication led to capital punishment. The wrath of the many against the actions of the few. “For the good of the group”, and all that. It also appears to have underpinned the success of inner-bands of in-groups to plan, plot and conspire against potential threats or opponents in the Game of Power. And this is where things get a bit squirley. When we select for traits of organised violence over reactive violence, we are opening ourselves up to corruptive agents who can use their proactive aggression to seem like they are taking action for the good of the group when in reality they are only looking to further their own individual positions within the groups power structure. Often this is at a detriment to the, “greater good”. So this leaves us asking a bit of an odd question: what type of aggression is best?

Force vs Force

It is funny how one branch of thinking can sprout another in a mindspace far removed from the original roots. Wrangham’s paradox got me thinking of my own. Lacking originality, I labelled it the Force vs Force Paradox. Focussed around the concept of force removal, the paradox is centred around the question of whether we can remove a force without using another force. The paradox is predicated on the belief that no we cannot; force removal requires another force. We will explore why I assume this later, but for now we can understand the paradox by noticing that, when removing one force with another force, the thing that is left is, yes: another force. On a surface-level, this defeats the original purpose of removing the force in the first place.

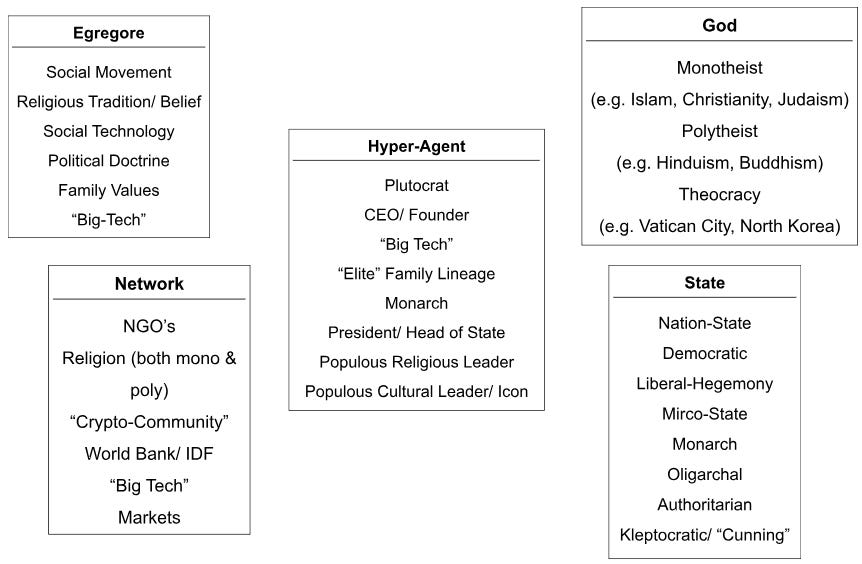

I know what you are thinking... what do I mean by force? In this case, (the case of group-dynamics) force is used to describe any entity (human-based-system) that is able to concentrate and utilise power to continue their own expansion. There are five main forces active on the global stage that have the true capacity to change that very stage for us all. They are: the state, god, hyper-agent, egregore and network (see endnote 2 for a more concrete description and examples for each of these forces).

Now, back to my earlier assumption that force cannot be removed without another force. Force - a form of power - obeys power laws in the sense of expansion or contraction. Whatever the case, force naturally moves objects (as it enlarges its size and sphere of influence), because of its use of power. Eventually, any force that is self-expanding (or contracting), that is dominating a certain space, will require replacement. Energy-sinks and obsoletion increase in the broader system over time. If the original force is not replaced, and is left to continue expanding or contracting, then it begins to encroach on the boundaries of others. Such expansion in itself then becomes a broader issue.

You may be wondering: if a force can become obsolete on its own over time, then there is no reason to remove it with another force in the first place. Force follows power and power seeks self-expansion until the critical mass of self-extinction is reached. I like to think of the Sun when I think of the ultimate example of this expansionist power dynamic. The sun burns until it self-extinguishes. In this self-extinction, it not only destroys itself but it destroys all components contained within the boundaries of its system. If you leave such a power to self-extinguish, the end result could be catastrophic. Moving closer to home, I like to think of Mother Nature - Gaia - when I think of force dynamics layered on top of a base power structure. To remove a force like Mother Nature (in no way am I advocating this) you would require another force capable of assembling more concentration of power. What type of force could replace Mother Nature?

Enter humans and our technology. In a highly interconnected global stage, the externalities of such obsoletion and natural self-extinction could cause the suffering of thousands, if not millions of people. As a new force on the block, we remove and replace the Amazon Rainforest with our industrial agriculture. We pollute our oceans and overfish to the point of extinction. In such a foolish attempt to replace Mother Nature, we are are leaving ourselves with two options: self-extinction or elimination by a more powerful force. The latter could be the Sun, or cosmic debris like asteroids, or a super-volcano like the one sitting under Yellowstone National Park. What then? Evolution, I guess. Another species (maybe those crafty ants?) will continue to evolve to become the next force on our planet - until, again, another more powerful force comes along. Is this paradoxical cycle of force vs force going to result in progression towards a protopian, sustainable, cooperative, and cohesive future? Are we destined to just keep bruteforcin’ our way towards more bruteforce? What sense is that? Do we even have a choice?

The Making Stream

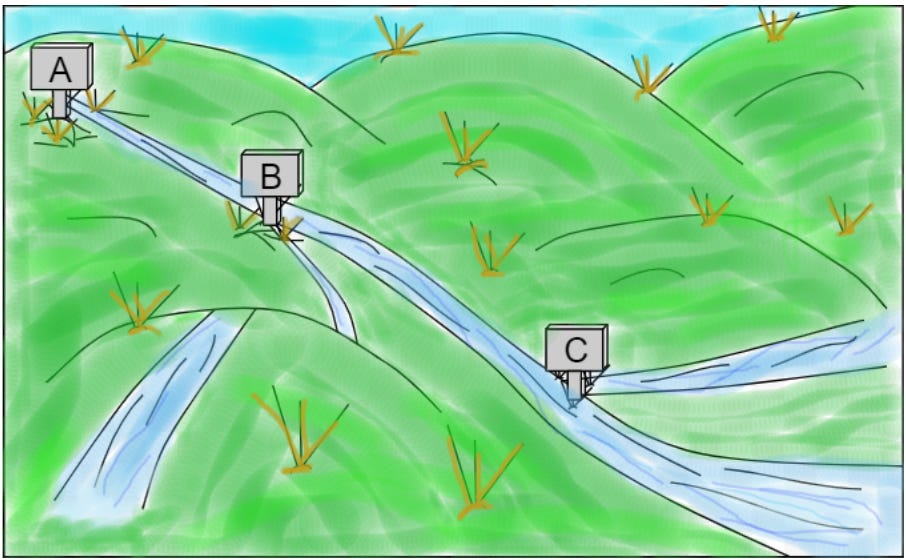

I recall a conversation I once heard between three novel, highly intuitive free-thinkers one bright summer's day. Sitting around a casual set-up of sofas and little else, cross-legged Daniel Schmachtenberger, Jamie Wheal and Jordan Hall were in the throes of discussing the topic of sensemaking. In its most fundamental sense, sensemaking is making the most accurate reading on the current reality around you and acting on it in an optimal, net-positive way. In an upcoming work on interconnectedness, in which I discuss sensemaking in greater detail, I illustrate this concept using the Making Stream. This visualises the downstream branches governing our perception and interaction with the reality around us. Alas, I am no artist, but please find a rough rendition of this illustration below. Save your kind words. If I had a five-year old, I would give them all the credit. I even coloured it in for your viewing pleasure.

Sign A represents the source of all our actions and behaviours. Akin to a high mountain spring, sensemaking is upstream of everything we choose to do. It informs everything we do. At the top, it all starts there. Midway downstream, at a branch of the now fast-flowing water, sits Sign B - our choicemaking. From A→B flows multiple choices - multiple adjacent possibles - forming future branches of direction. Then, at the furthest point down the Making Stream sits the final branch and the mouth of the stream - decisionmaking. You pick a choice to act on. You interact with your own reality and in so doing change your future trajectory by a few (or many) degrees. Could even a basic understanding of this Making Stream provide a means to escape our bruteforcin’ ways? The optimist in me sees proper individual sensemaking on a mass scale collectively leading to mass decisions being made that steer us away from bruteforce-based aggression. At least something - on a personal level - may change. “Think globally, act locally.” Anyway, for a more in-depth discussion on sensemaking and its role in global interconnectedness keep an eye on this space (or look elsewhere at the abundance of information out there - the aforementioned podcast being a good place to start) but for now, I digress.

Game Settings

In amongst the poetic dialectic emerging from this collective mindspace of complimentary and well-galvanised but not rigid ideas, came something I intuited to be revolutionary. Literally - I had to pause the video and take a minute. There are not many concepts that get ushered into existence and slap you around the face which still leave you smiling. Game B, for me, was that concept.

To grasp the settings behind Game B first you must take a step back and remember your alphabet. Let us first understand Game A, then we can circle back to Game B. In short form, Game A equates to Law of the Jungle type interactions. It is survival-based symbiosis. To understand this space, first think of the following question: is aggression more present in beings with (assumed) higher consciousness compared to those with lower consciousness? Without wishing to offend the panpsycists amongst you, let us just assume, for the sake of answering this question, humans have a higher level of consciousness than insects (I know, do not get me started on the collective hive mind of bees - it is just a thought-experiment). Beings with higher consciousness (i.e. us) tend to be able to control their aggression more than those with lower consciousness. We also have the capacity to generate maximal aggression, disproportionate to our size. Beings with lower levels of consciousness (in this case - insects) tend to always produce an averaged amount of aggression due to always being in a state of continuous Game A survival-based symbiosis. We (higher conciousness beings) have the ability to (temporarily) remove ourselves from this state by choosing not to react to certain inputs with acts of aggression. Hence the conceptualisation of another state of non-bruteforce existence - Game B.

I have been fortunate enough to spend time in both the Pacific and Caribbean coastal rainforests and jungles of Mesoamerica. Beautiful? Unbelievably. The “Coco-Locos” are to die for. Yet it is nothing personal per say but, if you were to lay down on the forest floor and did not move, I would give you roughly 72 hours - max - until you had vanished into the rich petrichor air and the damp foliage-littered floor. Dense concentrations of flora and fauna would not exactly enjoy picking parts of you off and feeding themselves or carrying bits of you back to their families. It is just survival. It happens daily as part of the intense environmental niche. Game A, at its core, represents such a survival-based symbiotic system. It has been happening forever, since prokaryotes slid around and began forming the multicellular eukaryotes which comprise all flora and fauna today. Survival, baby. Things get messy.

What is the big deal anyway? It has been happening forever. Let it continue. On a global scale, in the context of our species with our decentralised, fastly-approaching exponential technology (including weapons of mass destruction and weaponised artificial intelligences) Game A, even though it is the system nature has always taken to maintain a level of symbiosis, is perhaps not the best set of dynamics to choose to act upon under modern circumstances. Maybe letting it continue is in fact not optimal. As the international relations scholar John Mearsheimer puts it, the global stage is full of states acting in a system of interconnected survival-and-fear-based anarchy. Sound familiar? Yep. Game A on a global scale. Then, the revolutionary-era leather glove slap in the face…

What comes after A? If the first survival-based way of governing our reactions threatens to cause cascading catastrophes like nuclear disaster (perhaps reactive?) or a dystopian one-world governing surveillance-state system (perhaps proactive?) then surely - surely! - there is another choice, another fork in the Making Stream before our actions manifest these grim futures? Rejoice; there appears to be a turn up ahead. Scmachtenberger has labelled this alternative the Third Attractor. In his conceptual Network-State, tech-preneur and angel investor Balaji Srinivasan labelled something similar, but instead being one of four predictions he has made for how a near-term future world governance may structure itself. Srinivasan predicts three of these four possible futures as 1. American Anarchy - internal disruption and falling off as the hegemonic state - 2. CCP Control - China taking this position - or 3. International Intermediate - like India - taking over a Ray Dalio-esque “world order”. The fourth?Well, using the decentralised structure inherent to networks to recentralise the global incentives of modern nation-states, Srinivasan’s fourth option - his hybrid network-state - could provide the potential kinetic push towards Scmachtenberger’s Third Attractor: the interconnected, antifragile, cohesive world of Game B.

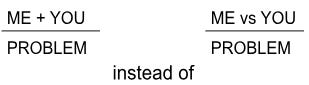

As far as I can gather, Scmachtenberger’s Game B space looks like a closed-loop materials economy, utilising renewable energy sources whilst remaining well within the carrying capacity of the localised biosphere, where governance is based off a proto-form of hegelian dialectic which equates to:

The latter being what our current governance system promotes. Game B architecture does not seem too far off from what the structure of Srinivasan’s theoretical network-state looks like. Starting as an online community that agrees to a set of shared values (making it aligned and cohesive), by pooling resources and capital from each other this spatially dispersed community can take part in “collective action”. Through the acquiring of physical territory in order to gain sovereignty from the state it resides in, the network-state materialises. In a decentralised network fashion, as more and more of these communities begin popping up across the world, options for movement, making direct change or staying loyal to a chosen community provides citizens with a full range of sovereign options when choosing which network-state to belong to. Citizens will no longer be held hostage by the state they happen to be born into. Hope being that such a decentralisation of state-based systems will lead to a net-positive recentralisation. Faster-moving network-styles of governance may increase the shared global incentives (like reducing pollution), shared global goals (like not having a nuclear war or dystopian surveillance states) and decrease government stagnation and inefficiency. Sounds kushty. Could the network-state be the catalyst for a Game B system to overtake our current Game A space?

Whilst we may, if we continue on our current Game A-aligned course, bruteforce our way towards a Game B-based harmony, it is hard to imagine. As Wrangham’s Goodness Paradox suggests, if we continue to select for proactive aggression in the process of self-domestication, we are simply replacing one form of aggression for another, not removing aggression from our global system entirely. It may be better to continue this way, or it may result in something we do not see (nor want) coming in our future trajectory. The Force vs Force Paradox suggests that even if we remove Game A-based forces with other forces, they will eventually reclaim the system. Contextualising such forces to the Game of Power that competing nation-states and other human-based entities play on the global stage suggests our system will simply continue on like nothing ever changed. The glimmer of hope rests in theoretical, conceptual forms of governance. It also rests within each of us. Using proper sensemaking (and a little inspiration from George Lucas) our own force can expand from within. Our own individual power will grow and permeate change locally. It makes sense when considering alternative forms of governance like the network-state as a viable mid-term solution. Growing in popularity and function, more and more new styles of governance may be tested, first in small batches, then on larger and larger scales. Some may turn out to be bunk. Others may result in net-positivity. Better than what we have, atleast. Maybe they become a means to stop our bruteforcin’ ways. Maybe the chances of regressing to a more aggressive state dissolve. Who knows, but worth a try.

1

“Once, when the world was threatened by a demon who could not be killed by any male being, human or divine, the gods imbued Parvati (Uma) with their powers. She became Kali, the wrathful, and quickly defeated the demon. But she did not stop there. Instead, she kept on dancing, threatening to destroy all life. Unable to stop her through brute force, her lover Shiva lay down in front of her, allowing her to trample his body, ending her rampage.”

2

Global Forces

References

Borofsky, T. Barranca, V. J. Zhou, R. Trentini, D. Broadrup, R. L. Mayack, C. 2020. Hive minded: like neurons, honey bees collectively integrate negative feedback to regulate decisions, Animal Behaviour, Volume 168, Pages 33-44,(Found at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S000334722030227X)

Dalio, R. 2021. Principles for Dealing with a Changing World Order. (Overview found at:

Mearsheimer, J. 2023. Featured on the Lex Fridman Podcast (Found at:

Scmachtenberger, D. Wheal, J. & Hall, J. 2019. Making Sense of Sensemaking. Featured on Rebel Wisdom. (Found at:

Srinivasan, B. 2022. The Network State: How to Start a New Country. (Found at: https://thenetworkstate.com/)

Wrangam, R. 2019. The Goodness Paradox: The Strange Relationship Between Virtue and Violence in Human Evolution.

This is an incredible insight into the multi-faceted ways on which our future depends. Excited to read more of your stuff!