A display from the Natural History Museum Magdeburg (image courtesy of Sven Sachs via X).

Being (Epistemically) Humbled

Sometimes in history we get things wrong. More often than not reconstructing reality, when the data is unclear, becomes a square peg in a round hole type of situation. Because those pegs looked cool, however, and because identity attaches itself to ideas, it can take a lot to admit to not knowing. Humbling oneself is a good place to start.

Basic exercises in humility come in many shapes and sizes.1 One easy way I like to routinely humble myself is imagining being born to another era. Luckily, with the dawn of Open AI’s “Sora”, you no longer have to imagine. Around the time of the last ice age, conditions were undeniably bleak. Subarctic, uncertain when the next meal will come, or whether you will become a meal yourself; for our ancient ancestors to make it through that… I can only pretend to imagine.2

Another method of taking ourselves down a peg is through the practice of “epistemic humility”. Epistemology - the study of what we know - is a philosophical gateway permitting access to unique spaces to think from. Humility is added, but it means more than admitting when you're unsure, mistaken or just about keeping your ego in check. Knowing where your knowledge comes from is about seeing and respecting expertise, without blindly following it. Even if that expertise is your own.

Epistemic humility was not high on the proverbial priority list for our ice age ancestors. Assumptions made about raw data were probably more acceptable. Those surviving the great freeze trusted their knowledge because it came directly from their own senses, or the senses of the handful of people they knew and trusted with their life. Humility was no doubt experienced, but humility to knowledge? What was the point? Epistemically, life was much simpler.

Of course these crazy conditions didn’t just oppress our ancestors - they proved oppressive to the flora and fauna sharing the bitterness too. One such creature roamed the desolate plains, the other propelled itself through the ice-ridden water. Paradoxically, both were equal parts powerful yet vulnerable.

In the past, when we have used mediums like archaeology, the humanities and the sciences to imagine these times and the things that lived in them (human or otherwise), the vision that overcame interpretation became pockmarked with fantasy. Elements like this stem from a place of unknowing. Interpretive gap-fillers: pegs forced into explanatory gaps.

In order to plug the holes and expel fantasy, museums - places literally created to evoke the “muse” - became centres of knowing. They, as it turns out, have also been places of unknowing.

Is That A… Unicorn?

Arriving in the summertime heat of Hanover, to the side of a polymath known for groundbreaking contributions to philosophy, mathematics, and science, what I like most about Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz is that he was the owner of a particularly strong optimism (and a pretty rockin’ haircut to go with it). We are, at least according to Leibniz, living in the best of all possible worlds. Not sure about you but in our current geopolitical climate I gravitate towards such a positive vibe.

Alongside his cheery demeanor and celebrated achievements, Leibniz repeatedly broke the seventeenth century mold and proposed ideas that, even by the standards of the dawning Age of Scientific Revolution, appeared on the fringe.

History tells us that hundreds of years ago was not an open, say-what-you-want kind of place. Recall less than a century earlier the Roman Catholic church burned Giodano Bruno alive for openly expressing the idea that other “worlds” may exist elsewhere amongst the interstellar highways of the great cosmic web.

Yet, undeterred (and safely tucked away in sleepy Germanic suburbia), Leibniz continued to speculate that, through mastering mathematics, a universal language could bridge “communication gaps” with, well, yes, anything steaming along those highways: aliens.3 Outlandish as it may sound to some, in many ways Leibniz was only foreshadowing modern SETI efforts. This flare, however, led Leibniz to believe in something else that even a child with a smartphone would balk at: a unicorn.

Reconstructed Magdeburg Unicorn (image courtesy of Nemoralis99 via Reddit).

Backtracking for a second, earlier we were in the middle of thinking about two creatures humbly buried deep in our icy past. The trace begins, coincidentally, not too far from Leibniz’s birthplace, near Quedlinburg, Germany, with the bones of a woolly rhinoceros and a narwhal. Here’s where it gets stranger.

Reconstructing reality is hard - it’s all about perspective. An accurate perspective is based on access to accurate data and the ability to interpret that data. Leibniz, for his vast knowledge, and despite his epistemic reputation for being extremely well-read, could not have observed all the data. In all fairness, no human can determine completely accurate information from all data. The compute is simply too much.

That being said it is, according to one famous sleuth, “a capital mistake to theorise before one has data.”4 Aside from potentially getting on the wrong side of Mr. Holmes, the result is that sometimes, when you really need an answer, the answer you seek does not exist. Well it does not exist, yet.

Theorising, it seems, is sometimes the only card left on the table. I can sympathise with this hand. Narratives can be woven with evidence, but evidence may not necessarily represent complete truth. Those interpretative gap-fillers begin to look quite fulfilling.

But Leibniz seemed to forget a crucial point, one highlighted in an interview with data expert Sarah Jarvis who said “data science is all about asking interesting questions based on the data you have—or often the data you don’t have.” Yes, at the time of observation an accurate read may be impossible yet, even if the data does not exist, or you cannot see it, good questions - according to the experts - may just save the day.

In his Protogaea, a book intended to develop “the seeds of a new science called natural geography”, the only interpretation of the data that made sense to Leibniz was layered with the fantastical. Hindsight is 20/20, but Leibniz was not thinking about what was missing from the picture and, only interested in what he could (and wanted to) see, Leibniz, for all his intellect, skipped a posteriori and jumped straight to a priori. Thus, a prerequisite for justifiable overconfidence appears to be strong epistemic humility.5

Consequentially for Leibniz, when trying to construct a “new science” the peg he forced into the interpretive gap meant he mistook the concatenated bones of a woolly rhinoceros and a narwhal for, well, what has been dubbed the “Magdeburg Unicorn.”6

Philosophical Entity

We create entities all the time. Religions are based on divine and spiritual entities. When a child switches off their night light, entities exist in the corners of the room, in the rattling of the pipes. Ontology: the study of what is “real”, is designed to parse out these entities to see which make the final phenomenological cut.7

Philosophical entities are similar, but with slight key differences. Whilst they are still created in a subjectivist sense: belonging to the unique meaningmaking of the individual observer, and so do exist (if nowhere else) in the mind of the observer, when trying to ontologically sort entities of the philosophical realm it may be best to adopt a constructivist framework: truth exists in both the individual interpretation of the entity, and the actual reality of the entity itself.

In the most basic sense Magdeburg Unicorns, as philosophical entities, are things that look like what we think they should look like, because we want them to look that way. By moving away from a purely subjectivist corner, whilst avoiding a complete overcorrection towards the objectivist corner too, we are able to maintain epistemic humility in a more pragmatic sense via constructivism in two ways:

Our observation of the entity is valid - it is what we see - and the meaning we place on what we observe has epistemic value.8

Our observation of the entity is not reliable - we don’t see what we don’t see, just the same as we don’t know what we don’t know, so we must factor in questions about what is not observed, and allow wiggle room for any epistemic error.9

Philosophical entities, instead of directing pilgrimages or giving us a fright, can be attached to various phenomena, real or philosophical, in order frame thinking. Entities like this provide “structural duality” to subsequent analysis: acting both as a constraint (setting the outer bounds of what we observe and make meaning out of10) and a resource for action (offering certain characteristics to measure phenomena against11).

Evidence12 turns into data, and data13 takes structure forming information.14 Knowledge15 emerges downstream. But when we don’t know what the evidence means - just like how Leibniz couldn’t fathom the anatomical differences between a narwhal and woolly rhinoceros - how can we be sure we are bottling perspectives from a reliable source?

When reconstructing reality we build unicorns because unicorns are genuinely what we see. In the case of the Magdeburg Unicorn, under the framework of epistemic basal relation: the relationship between a belief and the reason for that belief, Leibniz, already holding a personal bias toward fantastical natural phenomena, justified a belief in unicorns by using the pre-arranged bones in the Magdeburg Museum as his reasoning. Succumbing to improper basing, Leibniz justified his belief based on a reason not from his own direct observation, but instead from second-hand data that neatly fit his mental model.

Proper basing, on the other hand, would have required him to personally analyse each bone to assess its anatomical properties. Again, at that time, this would have been neigh-on impossible. Moreover, it wouldn’t have mattered; the knowledge we have now is not comparable to the knowledge he had then. Leibniz’s observation was not reliable because he did not know what he did not know. But is that his fault? Or is he just a product of interpretational change over time? I would argue his interpretation, his unicorn, was indeed valid, because the meaning extracted from the data logically justified his belief. Not sure about you, but I feel a paradox brewing.

Wanting to find something special, let’s capture some philosophically-grounding characteristics of a “Magdeburg Unicorn”:

Starting with a fun one: The Magdeburg Unicorn Paradox 1: whatever appears to be a “unicorn” now will not be a “unicorn” later. This means that, paradoxically, the entity possesses both the “is a…” and “is not a…” conditions simultaneously.

Role of data: a thing16 can only become a Magdeburg Unicorn when that thing is reconstructed using incomplete data or misinterpreted evidence.17 Data creates myth; unknowing fuels fantasy.

Value: imagined or not, Magdeburg Unicorns are pretty special.18 If something is one thing and turns out to be another thing, that thing, whatever it turns out to be, deserves attention. Additionally, the mythic element to the unicorn (myth at any scale for that matter19) adds epistemic value because it adds context. Context is key.

Understanding: in the very act of identifying, observing and trying to understand the true nature of the Magdeburg Unicorn, evidence will, at varying degrees, reveal itself. (Whether or not we know how to interpret that evidence is another question.) Thus, one way or another, when unpacked, the Magdeburg Unicorn releases some deeper understanding of reality, however slow the reveal is.20

Ending with an equally fun one: The Magdeburg Unicorn Paradox 2: something believed to be known, that is really an unknown, that leads back to a known. This loop of knowing/unknowing continues this way until objective, verifiable and rigorous scientific results are determined (if ever possible).

For a broader definition of our entity, three determining criteria are:

1. Interpretive gap filler.

2. Appealing yet inherently misleading construction.

3. Catalyst for deeper enquiry and knowledge expansion.

I guess the next step, after such a philosophical preamble, would be to go out into the wilds and wrangle ourselves a Magdeburg Unicorn. And that, my friends, is where we reach back to modern times.

Real World Philosophical Phenomena

Framed within the honest errors of a brilliant polymath, both long and short criteria in one hand, philosophical lasso in the other, where can we possibly begin to look for real world phenomena that satisfy the conditions necessary to be classified a Magdeburg Unicorn?

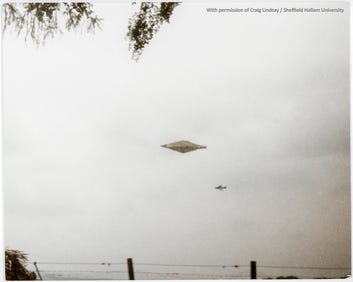

Now, I don’t want to argue over UAPs being “real” or not. I’ve made clear that I lean toward NHIs existing in some capacity or another, but, because I give us humans a lot of credit too, I also wouldn’t be shocked if it all ends up being part of a self-fulfilling evolutionary mechanism, or something else of the sort.21 Whatever side you sit, I want to stress: this is not about sides; we all get along. What this is about is the notion of unknowing, and we are all bonded in that.22

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

When I think of the modern UAP phenomenon - the reports, congressional hearings, theories, arguments, trickery and mockery alike - the story of Leibniz and his Magdeburg Unicorn becomes a somewhat slap-stick-yet-stark reminder to remain epistemically humble but, even moreso, a reminder to understand (and to also cut ourselves a little slack) that sometimes we are not seeing because we cannot see. It is just a little too far out of our scope of observation and understanding - at least in this thin slice of time pie.

Framed within the criteria above, UAPs are clearly an interpretive gap filler: we have no clue what is going on, yet we all have our own ideas, theories and interpretations, even if they remain behind closed doors, as to what could be happening. With all the multifaceted parts that make up the modern UAP phenomenon,23 the data making up the base topographical layer of the sensemaking landscape is confusing at best, utterly unnavigable at worst. Terrain ideal for sowing interpretative gap-fillers.

If you take the work of one of the Godfathers of the internet, and maybe the most respected UFOlogist of our time, Jacques Vallée, then we immediately see conditions for Paradox 1 within the UAP phenomenon: how interpretations of evidence have changed over both time and space. In other words, how UAP are both UAP and not UAP.24

Changing form, depending when and where, supports the constructivist framework. The fact that something is witnessed or recorded validates the experience, yet this changes case to case so is simultaneously unreliable. The UAP phenomenon also satisfies the notion of embedded “myth”, through both literally becoming part of cultural myth,25 to being a true myth unto themselves.26

Satisfying the second of our conditions, the phenomenon has so much “appeal” that it might as well be the “A” in UAP. From Hollywood hits, scores of memes, to breaking news headlines, UAPs are returning in full force to the modern zeitgeist. And, in this subtle “returning”, Paradox 2 is found. If you follow the US government's take on the UAP phenomena, from knowing they are weather balloons, and that there is nothing of scientific value, to now admitting complete unknowing, whilst agreeing that there is incomprehensible amounts of scientific value in studying the phenomenon in 2024, it becomes clear that we have gone from being sure of knowing to now being certain of unknowing. The not-so-subtle directionality suggests a completed paradoxical loop - a return to knowing - might be coming our way.

Yet, the “m” in “misleading” is the subtle missing consonant in UAP; whether from the phenomenon itself,27 or the attempts at intelligence gathering behind (or at) the scenes by groups with a vested interest in controlling the flow of information,28 looking closer at the UAP phenomena is like one of those infinite zoom arts: frustrating, but oh-so beautifully captivating.

Meeting the final condition, by their very nature, UAP, and the attempts to understand the phenomena, just like a Magdeburg Unicorn, leads us to further and more accurate reconstructions of a constantly evolving reality. Contemplations on faster-than-light space travel, the study of electrogravitics, complex materials science, theorising about development of life in various conditions, and philosophical musings around what it means to “not be alone” in the universe all branch out from just a cursory look into the strange phenomenon.

A Return to Humility

Now I am aware I run the risk of self-contradiction: writing about epistemic humility whilst at the same time partaking in speculative thinking about a completely anomalous phenomenon like UAP… I get it. Instead of making speculative assertions perhaps it best I steer my narrative towards the beacon of cautious enquiry alone, at least before I crash into something I cannot see coming.

Whatever the case, whether it be hundreds of years ago with the Magdeburg Unicorn, or today with phenomena like UAP, scientists, governments, the media, the good old fashioned public, you and I, will always be drawn to a fantastical story. It makes sense: in many ways our very existence is fantastical. The gravitational allure is simply far too strong. Reporting on a Magdeburg Unicorn garners attention, attention garners minds, minds garner interpretations and, eventually, through all the inevitable wrong turns and dead ends, we may get a glimmer of that elusive knowing at the end of the tunnel.

When we connect dots, we may find a unicorn. The question is: is that unicorn real, imaginary, or somewhere inbetween? If real, if there are valid and reliable interpretations of the data, strong epistemic basal relations, and perhaps a good bit of gut intuition, you may have come face-to-face with a Magdeburg Unicorn. Stop stare, and smile to yourself; unknowing comes in many forms; knowing, it seems, comes in many more.

Getting crumpled in a full contact sport, or narrowly escaping getting your head kicked or neck choked in a martial art, is another way. So is talking a stroll into any incomprehensibly grand and complex architectural wonder, like the Sagrada Familia, or across an ancient wonder, like Machu Picchu. One more for good measure: learning a new language - and yes, Duolingo does count.

Even just thinking about existing in those conditions, removed from modern creature comforts, is enough to make me never complain about the British summer ever again. Until next summer.

NHIs, UAPS or the good ol’ fashioned UFOs in modern vernacular.

“Magdeburg” because that is where the Museum für Naturkunde museum is located, and “Unicorn” because, well, to be completely fair, the bones had already been reconstructed in their fantastic form by another Prussian scientist, Otto von Guericke, and were displayed in this quasi-unicorn state before Leibniz came to observe them. Leibniz chose to see the unicorn set before him.

See the framework for phenomenological analysis laid out in: Streiber & Kripal, The Super Natural, 2016.

Especially in the Second-Order Cybernetic sense of how observing a system can change not only that system, but the observing system too. A cyclical interplay between observer and observed.

While an argument can be valid (the conclusion logically follows from the data), if the data is inconsistent or changes frequently, it lacks reliability as a basis for complete truth.

If someone was to go round making meaning out of every single thing they saw, then they would probably not get much done, just the same as if somebody could see no meaning in anything at all they would probably not be the nicest person to talk to. A philosophical entity can be used to make meaning out of something, but sets a sort of limit to that meaning by bounding it within the characteristic confines of the entity.

Take the following example: we see a light in the sky. We have a mental model based around what we know to be in the sky: an airplane, a helicopter, a bird, a drone, a cloud, lightning, stars etc. When we see this light, we go down the list of possible interpretations, trying to ascertain which one is correct. Characteristics in this case might include, was it bright, only for a second, and accompanied by a noise? No? Not lightning. Is it day time? Yes. Not stars. Did it move quickly across the sky? Yes. Not a cloud. Was it large? Not a bird or commercial drone. Did it have rotor blades? No. Not a helicopter. Did it fly in one straight line? No. Not an airplane. We go through the list of characteristics based on the different mental models we have, for what we expect to see in the sky. The philosophical entity just lets you do this quicker, because the characteristics are pre-programmed into the entity itself.

“Evidence” refers to the raw, unprocessed reality - observable phenomena, objects, patterns, or signals that exist independently of interpretation.

“Data” arises when evidence is captured, measured, and categorised through different tools (thermometer), methods (thermistor), and frameworks (Fahrenheit).

“Information” emerges when data is organised and contextualised to convey meaning or patterns, involving the interpretation and relational structuring of the data collected.

"Knowledge" emerges when information is synthesised into a coherent understanding that allows for theories (natural selection), explanations (why finches on certain islands have shorter beaks due to a lack of hard seeds), and predictions (birds with intermediate beak lengths will have a survival advantage in environments with mixed seed types).

Philosophical (metaphysical object) or real (physical object).

Travelling linearly down the knowledge chain, there is a lot of room for “interpretation” before something becomes embedded in our belief system or value/ goal structure (e.g. data - interpretation - evidence - interpretation - information - interpretation - knowledge - belief and value systems). This can have cascading epistemic effects like the distribution of wrong knowledge, or restructuring entire belief systems around weak epistemic basal relations.

Whatever the underlying thing ends up being, a Magdeburg Unicorn is something you want to enquire about because, well, if childhood teaches you nothing else, unicorns are pretty damn cool.

In Leibniz’s case, his unicorn ended up morphing into two distinct species, and now we know the anatomical difference between the bones of a narwhal and that of a wooly rhinoceros. We also have a case study in misidentification of fossil remains, and can frame this error in epistemic humility to avoid the same mistake in the future. Lots to unpack!

Alright; I would be a little shocked.

Despite inaccuracies and even a misleading nature, the philosophical value of provoking curiosity and deeper investigation serves as a placeholder for further exploration and refinement of knowledge. Over time, the scrutiny of such constructs often leads to more accurate models, shifting paradigms as more data becomes available. The Magdeburg Unicorn, while initially a flawed representation, becomes a stepping stone toward greater understanding rather than remaining a permanent error.

The list is endless, but I direct you to the opening section of my previous article “Self-Fulfilling Evolution” to get a fairly comprehensive overview.

For example, transforming from shields and wheels in the sky, to religious experiences, to folklore of fairies and goblins, to “airships”, to unfathomably high tech-crafts, all depending when and where experience happens.

See: Diana Pasula, American Cosmic (2019) & Encounters: Experiences with Non-Human Intelligences (2023).

There is still no clear consensus - at least not one being shared publicly - about what the phenomenon actually is. It’s mythical status, however, is clearly felt all over the planet.

Trickery as discussed in Vallée’s Passport to Magonia, 1969, Messengers of Deception, 1979 and Revelations, 1991.

See: Richard Dolan, UFO’s & The National Security State 1 & 2 (2002 & 2010), or watch the fantastic new documentary “The Programme” from director James Fox.

![r/SpeculativeEvolution - I decided to photobash the paleoart of the infamous 17th century Magdeburg Unicorn [OC]. r/SpeculativeEvolution - I decided to photobash the paleoart of the infamous 17th century Magdeburg Unicorn [OC].](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!X-pK!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F8c99db3f-44c6-41c7-8c7a-cbe7d637f631_4133x3625.jpeg)