It has been a few years since I was fortunate enough to speak with residents of nearby towns, our talks seeming to always come back, in a roundabout way, to the boundless mysteries that the archipelago has yet to offer any meaningful answers to.

A hurdle in the way of many Western researchers wanting to learn about megalithic Japan is the shroud of mystique that coalesces around the history of the combined 6,800 islands that piece together the archipelago of Nippon - a place where the Sun originates.

Speaking to people from across Japan, one gets a sad sense that the Japanese government does not care much about these monuments. Hundreds, if not thousands of sites go unrecognised by Japanese officials. Care, funding and research is often nowhere to be seen. Fortunately, many of these misunderstood megaliths are protected by their adoption as sacred sites by the numerous ancient religions practiced to this day - Buddhism, Shintoism and Taoism, to name a few. Traditions of a sacred nature seem to recognise sites of an equally sacred nature, even if they were not originally theirs. With sacred bound to sacred we now have the time and space to explore what these mysterious Japanese sites are really about.

Ishi-no-Hoden

We begin our journey in the Hyōgo Prefecture of the Kansai region. Whilst it’s spring, you may witness the picturesque scene of cherry blossoms on the surrounding trees, gently blowing across the foreground of Himeji Castle, the air filled with subtle blush-pink snowflakes. However, that is not what we have come to look at.

Lying approximately 11 kilometers (7 miles) to the southeast of Himeji Castle, near to the town of Takasago, is the aptly named Stone Sanctuary. Secluded, peaceful, and a little bit mind-boggling, admittedly, “lying” does Ishi-no-Hoden no justice - the close to 500-ton megalith miraculously has the illusion that it’s “floating” upon its watery base, providing the basis for the local name - Uki-ishi - meaning Floating Stone.

It’s true that the weathered megalith appears as if some strange force is allowing it to balance breathlessly upon the open, spring-fed water (believed to be the case since the shrine's records state it never dries up, even through severe drought).

However, upon closer inspection, the only strange force at play is the precision-cut engineering that’s allowed the excess rock to be cropped away, suspiciously tight to the megalith’s base, providing a steep internal gradient to the edge approaching the surrounding water, delicate enough to pull off the trick of engineering, strong enough to withstand Japan’s punishing seismic routine.

An important site in megalithic Japan is the ancient Ishi-no-Hoden megalith or Floating Stone, which can be found in the Hyōgo Prefecture of the Kansai region. (image courtesy of z tanuki / CC BY 3.0)

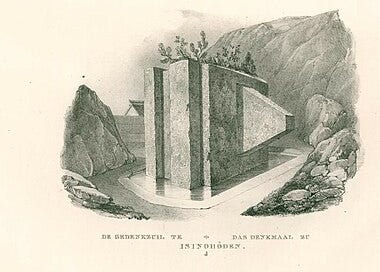

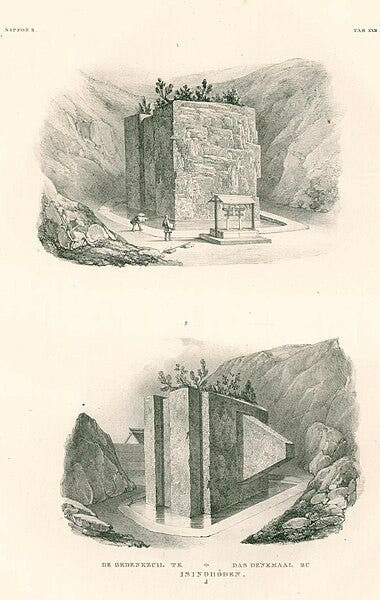

Ishi-no-Hoden megalith or Floating Stone, plate in Siebold's Nippon (1832–) (Nippon II Tab. XXIII) (Image with permission Nippon Atlas. n.5" Kyushu University Library Collections)

Ishi-no-Hoden, in all its angular glory (CCO 1.0)

Close to two centuries later, through 2005 to 2006, the University of Otemae and the local town council “conducted three-dimensional laser measurements and carefully studied the nature of the surrounding rock”, concluding it was formed of hyaloclastite, a form of volcanic accumulation from activity millions of years ago (Pavlik, 2018).

Whilst there are no clear tooling marks around the stone itself, one can only wonder how long it’s been sitting there, and what type of weathering erosion may have worked away at it over the suspected thousands of years since its initial alteration by our ancestors.

Another Sage?

Ishi-no-Hoden draws stylistic similarities to other sites in Japan, like the mysterious Masuda-no-Iwafune megalith in Asuka, Nara Prefecture.

Masuda-no-Iwafune - “The Rock Ship of Asuka” - (images courtesy of Saigen Jiro/Wikimedia Commons CC0 1.0)

If we stick on the vein of stylistic similarities for a minute, I would be remiss if I did not mention the stylistic comparison between these two megalithic sites (and many others like them across the Japanese Peninsula), and sites I have personally visited over 15,000 kilometers away, in South America, specifically Peru.

Top: The front of Masuda-no-Iwafune (left) and the back Masuda-no-Iwafune (right) (images courtesy of The Ancient Connection).

Bottom: The Rumihuasi Stone of Apurimac, Peru (left) and the nearby Sayhuite Stone (right) (images courtesy of Inca Trail Machu)

Top: Angular features of Ishi-no-Hoden (left) and carved granite block with “holes and channels” from Asuka (right) (images courtesy of The Ancient Connection).

Bottom: Angular blocks from Puma Punku, Tiwanaku, Peru/Bolivia border (left) and carved andesite with “holes and channels” from the same site (right) (images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons).

Left: Stonework from Asuka, Japan (image courtesy of The Ancient Connection).

Right: Stonework from Puma Punku, Peru/Bolivia (image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons).

But I do not want to get too ahead of myself here. Returning, for now, to Japan, when historical context is in doubt, which is certainly the case at the Ishi-no-Hoden and Masuda-no-Iwafune megaliths, turning to local belief systems and mythological traditions can reveal information that may have been purposefully recorded amongst the layers of narrative and fantasy.

Protective Shinto shrine at Ishi-no-Hoden (image courtesy of z tanuki / CC BY 3.0).

Starting with the Shinto shrine that has amalgamated with the space immediately surrounding the mysterious Floating Stone, could it hold some clues, albeit vague, to the true genesis story of this megalithic marvel?

The shrine tells how the kami known as Okuninushi (“Onamuchi-no-kami”) once ruled over the land of Izumo, modern day Shimane Prefecture, approximately 115 kilometers (71 miles) to the northwest of the home of Ishi-no-Hoden.

Kami are traditionally divine spirits (appearing both as natural and anthropomorphic manifestations) in the Shinto religion. Represented in the earliest Japanese folklores, it is known, rather intriguingly, that there is an “ancient association with kami activity and epidemic diseases, floods, and drought” (Chilson & Swanson, 2006, p. 19).

Both figures of spiritual significance and leading figures in narratives spanning millennia, accounts of divine figures appearing after, or immediately surrounding, ancient catastrophes is nothing new to mythological systems worldwide. It is a similar narrative found across the planet, and Peru is no different. Whilst we will get to this in due time, the surface-level stylistic comparison shared across the Pacific rim certainly becomes a little more intriguing.

Amaterasu, one of the central kami in the Shinto faith. (Utagawa Kunisada / Public domain)

Stories Set in Stone

Many countries situated around the Pacific Ocean seem to draw parallels with one another, suggesting at one time there was at least one common connection between these amazing yet still so unknown settlements. It makes sense, we know our ancestors were ocean voyagers, even thousands of years ago. We have seen transoceanic connections in megalithic masonry, we have hinted to it in foundation mythology, and now it may also be seen throughout ancient sculpture.

The meaning behind the Japanese “dogu” is still unclear, but it is known that these mysterious Neolithic stone figurines appeared during the Jomon Period within ancient Japan, a strange and undoubtedly unknown time, starting around 14,500 BC and ending close to 1000 BC. The level of detail found in some dogu suggests an exceptional skill of craftsmanship - some are even completely hollow but still able to stand freely on their own.

Theories range on their purpose. The Japanese Times reports how some researchers believe artifacts such as these were designed as “play toys”... the prevalent theory before this was that they were simply ritualistic offerings. Dr. Kaner, an archaeologist specializing in prehistoric Japan from the Sainsbury Institute for the Study of Japanese Arts and Cultures believes “there is scope for both ‘everyday’ figures and objects of veneration within the dogu tradition.”

Dogū (clay figure), Jomon period, 7000-400 BC, Tokyo National Museum. (CC0)

The truth is, nobody really knows what these artifacts were used or designed for. Many researchers tend to believe they often represent real historical figures, used to venerate people whom the local population looked up to. This certainly makes sense. From the Egyptians to the Romans, and even in our modern times, we seem to have a penchant for creating large stone sculptures of historical figures we want to idolize.

We know that to be the case with the civilizing figure Tiki, who was traditionally immortalized through stone sculptures found throughout the numerous Polynesian and Pacific islands, thought to have originally represented this civilizing figure himself. In fact, some Polynesian depictions of the founding hero Tiki draw eerily similar senses of artistry to the mysterious dogu figures of prehistoric Japan.

Pacific Passageways and Tiki

When compared side-by-side, there seems to be an, albeit small, stylized similarity between the “goggle-eyed” dogu from Kamegaoka, the Tōhoku region of northern Japan, and a variation of Tiki of the Polynesian islands across the Pacific.

Most intriguing, the large round, almost oval eyes, both feature horizontal lines separating the center – which is not typical for human eyes - and the fact it appears on both is interesting. Also, while not shown in the given example, many Tikis also featured geometric patterns, as seen on the body of the dogu.

Right: The “goggle-eyed” dogu from Kamegaoka, late Jomon period (1,000- 400 BC) (CC BY SA 4.0).

Left: A Tiki sculpture found in the Marquesas Islands, French Polynesia (Public Domain).

Admittedly, the similarity is small. But could exploring the history of the Tiki help provide some clarity?

I contacted an Oceanic Art specialist and, while I’ll omit his name, I can say that he works for a very prestigious and long-lasting antique auction house and dealership business. Among a multitude of interesting things, he pointed out that there is a considerable “...lack of historical material documenting the precise provenance” regarding these (Tiki) sculptures.”

“Most of these objects have been collected randomly… without any written documentation [and] arrived in Europe in the late XIXth century” he went on to tell me, ending his correspondence by making clear that we should “not exclude them from being older than from this time.” Thus, just like the dogu, we are left rather unsure as to where, when, or why these Tiki sculptures appeared in the Pacific Islands.

Could there have been some sort of oceanic connection between Japan and the rest of the Pacific, from Polynesia to Peru, that spread stylistic similarities? Could it have come from one single, ancient source?

A 2012 study of edge-ground axe heads in Japan, dating to 38,000 - 32,000 years ago (Takashi, 2012, Pp. 70-78) certainly highlights the fact that, due to the heads being created from obsidian, a material only found on the island of Hokkaido, the earliest humans in Japan would have enjoyed access to sea-faring crafts which allowed them to process this sought-after material.

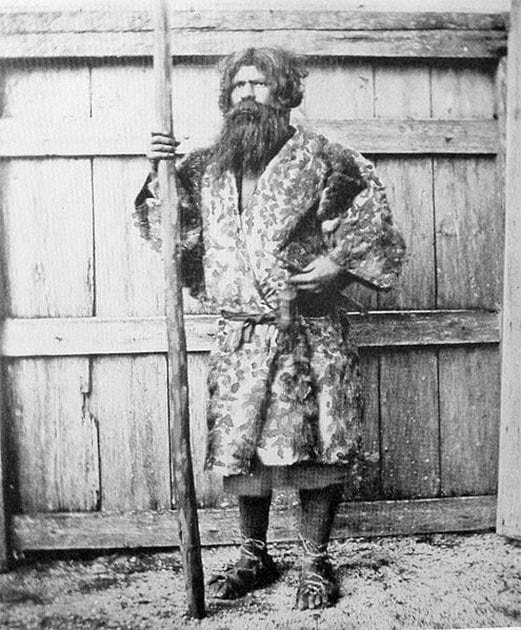

An Ainu man, one of Hokkaido's indigenous people. (Public Domain)

The distances would have started small but, according to archaeologists Glascock and Kuzmin, they eventually rose to over 1000 kilometers (621.37 miles) during the Upper Paleolithic (around 50,000-10,000 years ago).1

While this is not conclusive proof that Japanese islanders were in contact with South Pacific populations or vice versa, the mechanism by which some form of prehistoric transoceanic connection could have been made is plain to see. And the connection continues to spread the more we look.

Further Afield

The intrigue continues when we learn that this superficial artistic link does not just stop with these Pacific cultures. I have also noticed a similarity between various dogu sculptures and figures found in the Lepenski-Vir archaeological site. This is located all the way to the west, a journey of, as the crow flies, over 8,000 kilometres (4970.97 miles) in modern day Serbia.

From Ph.D. research in the Department of Archaeology within the University of Cambridge, Dr. Borić claims the Serbian site dates back to 8,200 BC and the so called “Progenetrix” sculpture is from the 7,000 BC strata2 - well within the Jomon time period.

Left: The Lepenski-Vir “Progenetrix” figure (CC BY SA 4.0)

Right: Dogu counterpart (Public Domain).

Obvious similarities arise:

The facial expressions - notably exhibiting a look akin to “shock” or “surprise.”

The small, circular, ringed eyes, both seeming to be deliberately depicted looking up.

The rounded, triangular shape of the face.

The geometric-style pattern engraved around the body.

The position of the hands - seeming to curl inwards, resting on the torso.

With the notion that the Japanese Jomon period lasted for close to 14,000 years, the possibility that they were in contact with areas as far out into the Pacific as Polynesia, or as far overland to Serbia, does not seem too out of the realm of possibility.

This pattern of information transferral, west across Eurasia, eventually to Serbia during the Lepenski-Vir period, and also south-east by means of oceanic voyage down to the Pacific Islands, is intriguing because, as we shall see shortly, there are genetic migration patterns that also match this flow of information.

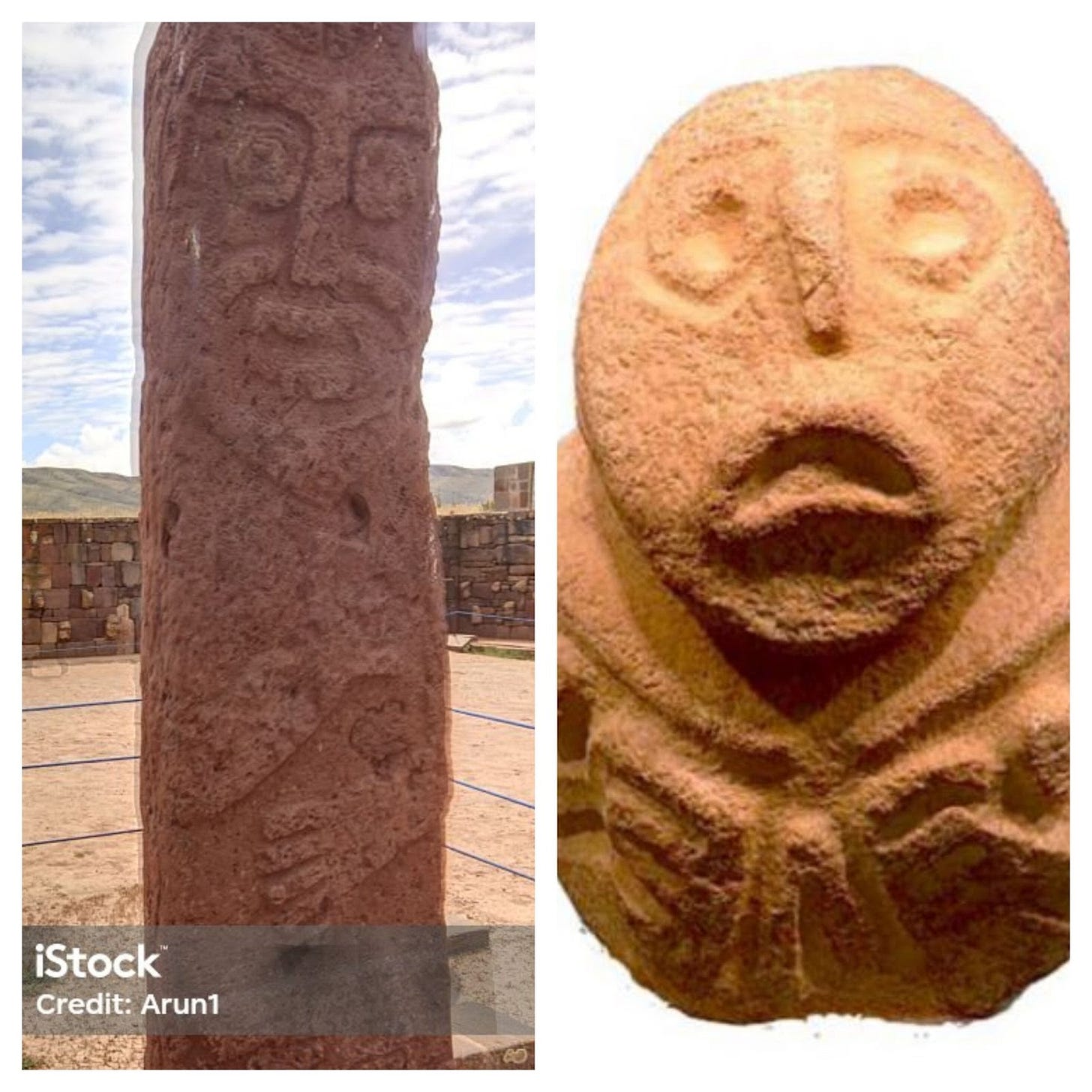

When we also notice stylistic similarities between sculptures between Japan, Peru/Bolivia and across Eurasia and into the Eastern Europe (see below), and then factor in additional stylistic similarities between megalithic stone work and systems of mythos, we move past the slight stature of sculptural figurines alone and enter into the realm of a strongly correlated “megalithic Pacific” connection.

Left: “Viracocha” - the Andean “kami”, immortalised at Tiwanaku, Peru/Bolivia border (image courtesy of Cory Canuel).

Right: Dogu, from Japan’s deepest prehistory, (Public Domain).

Right: Perhaps another rendition of “Viracocha”, at Tiwanaku, Peru/Bolivia border (image courtesy of Arun1).

Left: The Lepenski-Vir “Progenetrix” figure (CC BY SA 4.0).

Megalithic Pacific Networks

Archaeological findings indicate that beliefs and reverence of kami were taking place well into the Jomon Period, which we know potentially spanned all the way back to 14,500 BC, before the potentially catastrophic Younger Dryas Boundary - the beginning of the end of the Earth’s last ice age.

Adding to this interest, returning once more to hillside of Ishi-no-Hoden, Okuninushi - the kami attributed to the megalith - was recorded as a great builder, one who retained secret (seemingly hermetic knowledge), fabled for his abilities to heal and encouraged marriage to take place.

Extremely similar to symbolism alluded to in previous articles, myth depicting other sage-like gods throughout the world, including Cecrops in ancient Greece, Kukulkan (or Quetzalcoatl) of Mesoamerica and Oannes from the Fertile Crescent of ancient Mesopotamia are just a few far-reaching strands in our growing web of connection.

The local Shinto myth notes how Okuninushi was in the early stages of creating a magnificent monument, with Ishi-no-Hoden being the first piece shaped and put into place, when a neighboring rebellion left him distracted and his work unfortunately remained unfinished.

Standing (okay - floating) at 7.4 meters (24.3 ft) tall, the stone has a width of 6.5 meters (21.3 ft) and whilst it is mentioned in the Harima Fudoki (one of Japan’s earliest written records dating from 714 AD), it is mere speculation as to who created it - when and more importantly, how are still firm unknowns.

Astronomical Alignments

The connection Ishi-no-Hoden has to other unexplained megaliths from across the Pacific is certainly amplified when unlock the Pandora’s Box that is astronomical alignment.

I got in touch with Amelia Sparavigna, a physicist working out of Turin, Italy, and a member of the renowned American Physical Society (APS), who is a prolific investigator of potential astronomical alignments of various ancient sites around the world, including China and Italy. Having cited her research in a theory I proposed for the original purpose of Sigiriya, Sri Lanka (published in Ancient Origins E-Magazine), I was intrigued to see what she thought of Ishi-no-Hoden.

Amazingly, Sparavigna determined that there is a viable astronomical alignment resonating throughout the Floating Stone.

Admittedly a lot of the astronomical vernacular was hard to grasp, however, using a combination of Google Earth, The Photographer's Ephemeris and an experienced eye for astronomy, Sparavigna made clear that due to the ancient lunisolar calendar system, the alignment present at Ishi-no-Hoden (which lays across a 108° north-south axis) may represent an orientation to an interval that when “evaluated according to the sunrise on days of new Moon at the beginning of spring” is aligned to “the second new Moon after the winter solstice.” The new Moon of spring happens on a day, which is ranging between the 22 January to February 19. But what does this mean?

The alignment of 108° along the north-south axis, which Sparavigna first ascertained before conducting further, in-depth astronomical research. (Provided by the author)

Such an alignment suggests that the people who created the megalith of Ishi-no-Hoden had a) been well aware of astronomical alignments, and b) had the astronomical knowledge readily available to put this alignment into action. This is certainly intriguing given the surrounding myth of the stone’s kami creator, Okuninushi, who was revered for his hermetic-style knowledge.

Moreover, the lunisolar calendar is unique in that it tracks both time through the solar year (like a regular solar calendar - of which the currently used Gregorian calendar is based off) as well as indicating the current moon phase - predicting what constellations the full moon will appear close to.

Next, she used The Photographer's Ephemeris software to get an understanding of the potential astronomical alignments, and then used her expertise in the field to understand what they mean. (Provided by the author)

Whilst we are now beginning to realize that methods for tracking lunar phases have been around for over 34,000 years,3 it's also well established that ancient cultures tracked the passage of the Moon in order to ascertain low and high tides for maritime travel.

We further learn that when “the Sun, Moon, and Earth are in alignment (at the time of the new or full Moon)” [boldness added for effect], this creates “extra-high, high tides, and very low, low tides”.4 Thus, the alignment that Ishi-no-Hoden contains is directly connected to the time of year where extra high or low tides, also known as “spring tides”, occur. Information of vital importance to any civilization with maritime capabilities.

Whilst it might be surprising to some that the makers of these megalithic stone monuments also had vast astronomical knowledge also, which they used to align and encode their megalithic masterpieces, if we just think to some of the interpretations of one of the world's oldest (if not the oldest) megalithic site in the world, Gobekli Tepe, and how the stone pillars are adorned with cosmic symbology, then this megalithic-astronomical connection is noticed at the dawning of our history.

Certainly locals living deep in the Peruvian Andes were not surprised when the observations of Salazar Garcés, the Scientific Director of Planetarium Cusco, keenly noted the “axes of the Ñaupa Waka stone altar, projected at certain times of the year, point to positions of stars and constellations…”.

All across the Sacred Valley of Peru, megalithic marvels are thought to be astronomically aligned.

The strange, almost out of place, stone altar at Ñaupa Iglesia, in Peru’s Sacred Valley, whose three precision-cut “chambers” each align to certain azimuths, and thus specific celestial bodies during the year, in a similar vein to the Sigiriya complex and to the monuments of Egypt. (Misterios Con Xana/ CC BY NC SA 3.0)

So now, across the megalithic pacific, we not only share stylistic similarities between traditional artwork, we also share similarities between megalithic architecture and astronomical alignments. The case for a megalithic informational network spanning the Pacific Rim deep in our prehistory strengthens bit by bit.

The “Hominid X-Factor”

There are, if you care to look, quite obvious overlaps between the Megalithic Pacific information network and the ancient information lineage I have been investigating in my other article series. The predominant reason being the flow of hominid migration, following a specific gene - that of the Denisovans.

Perhaps east, reaching into the western shores of the Japanese archipelago, then travelling down through the Pacific Island chains housing the Tiki’s and across, east, to South America, where the information is encoded in Peruvian sites for all to see. Another wave, instead of travelling south, could have headed west, overland, and ended up past the Caspian and Black Sea regions, towards Siberia, where the site of Lepenski-Vir is situated.

I am of course talking about those descendents who converged with the Denisovans along the Siberian plains and the Tibetan Plateau. Those descendants who may have not only spread their genes and culture, but also key information regarding stone work, geometry and astronomical knowledge. All things we see evidence for along the Pacific megalithic highway. And genetic research supports this idea.

Migration of Denisovan genes, south down Asia, east to Japan, and north to the America’s (from beyond the paywall of Peyregne, Slon & Kelso, 2024, Nature article).

Migration and convergence points between our ancestors and other hominins - note route to Denisova Cave, Russia and between China and Laos - two important routes for our informational mystery (image courtesy of Natural Earth Data).

Genetically, Funadomari Jomons of Hokkaido “shared as much Neanderthal and Denisovan DNA as other Native Americans and East Eurasians” whereas Sanganji Jomon of Tohoku shared similarities with “implies genetic affinity of the Jomon people with Neanderthals”. What this suggests is that, at the very least, the Jomon people of Japan - the archipelagos earliest known inhabitants, share a mix of DNA from both Denisovan and Neanderthal groups.

Genetic connections not only exist between North America and Japan, but also span from Japan and Meso- and South America too.

Whilst I will leave this one where it is, for now (mainly because new genetic discoveries are being made every month, and more corroborating data will probably be released soon), the picture that has emerged may be summarised by:

Stylistic similarities between megalithic architecture, stone sculpture, mythology and astronomcal knowledge connect ancient sites across the Pacific, from Japan, Polynesia and Peru. The groups of people responsible for these sites may also be genetically linked, especially regarding East Asian populations, notably in this case, early Japanese inhabitants like the Jomon and Ainu, and notably early inhabitants of the America’s.

The tapestry being woven before us indicates that the Megalithic Pacific was indeed a thriving highway of information regarding masonry, astronomy, belief systems and transoceanic voyage.

Sites that have been hidden away from the public, in lands that have traditionally been isolated from the rest of the world, may hold clues as to where this information lineage originates from. The only way forward is to keep scouring these sites, probing for more questions to ask.

I’d like to thank Amelia Sparavigna for her patience, kindness and much-appreciated enthusiasm lent to me during our many discussions, as well as my Japanese students who really sparked my interest in this spirited, unknown and yet so historically-rich part of the world.

Note: this article is an amalgam of two previous articles, originally published on Ancient Origins, under the titles of “Ancient Mariners: Transoceanic Voyages Before the Europeans” and “Unravelling the Lesser-known Laser-sharp Cuts of Megalithic Japan”. As such, Ancient Origins reserves all rights to these original publications.

References

Borić, D. 2002. The Lepenski Vir conundrum: Reinterpretation of the Mesolithic and Neolithic sequences in the Danube Gorges in Antiquity. 76 (294), Pp. 1026-1039. [Accessed: http://orca.cf.ac.uk/39454/1/Antiquity-2002.pdf

Chilson, C. Swanson, P. L. 2006. Nanzan Guide to Japanese Religions. University of Hawaii Press.

Cotterell, M. 2003. The Lost Tomb of Viracocha: Unlocking the Secrets of the Peruvian Pyramids. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Glascock, M. D. Kuzmin, Y. V. 2007. Two Islands in the Ocean: Prehistoric Obsidian Exchange between Sakhalin and Hokkaido, Northeast Asia in The Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology. 2.1. Pp. 99-120.

James, V. October, 2009. The dogu have something to tell us in The Japanese Times. [Accessed: https://www.japantimes.co.jp/culture/2009/10/02/arts/the-dogu-have-something-to-tell-us/#.XlTD8JNKjOR]

Macey, S. L. 1994. Encyclopedia of Time. Taylor & Francis.

Malaspinas, A. S. et al., November 3, 2014. Two ancient human genomes reveal Polynesian ancestry among the indigenous Botocudos of Brazil in Current Biology 24/21, Pp. R1035-R1037

Matisoo-Smith, E. Robins, J. H. June, 2004. Origins and dispersals of Pacific peoples: Evidence from mtDNA phylogenies of the Pacific rat in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 101 (24) Pp. 9167-9172. (DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0403120101)

National Ocean Service. 2005. Tides and Water Level: Tidal Variations - The Influence of Position and Distance. (Accessed: https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/education/tutorial_tides/tides06_variations.htm)

Pavlik, J. 2018. The Monument is Called Ishi-no-Hoden in SUENEÉ UNIVERSITY [online] (Accessed: https://no.suenee.cz/monolit-jmenem-ishi-no-hoden/)

Shortland, E. 1882. Maori Religion and Mythology. Longman, Green: London.

Siebold, P. F. 1832. Nippon; Archive for the description of Japan, and its neighboring and protected countries: Jezo with the southern Kuril Islands, krafto, Koorai and the Liukiu Islands, according to Japanese and European writings and own observations. Leyden: CC van der Hork (Accessed:https://catalog.lib.kyushu-u.ac.jp/opac_detail_md/?lang=0&amode=MD820&bibid=1906469#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=23&r=0&xywh=117%2C-122%2C4252%2C7041)

Silver, C. March 2020. The Top 20 Economies in the World: Ranking the Richest Countries in the World in Investopedia. (Accessed: https://www.investopedia.com/insights/worlds-top-economies/)

Soderman. The Oldest Lunar Calendars in SERVI [NASA online]. (Accessed: https://sservi.nasa.gov/articles/oldest-lunar-calendars/)

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. January 2016. Ōkuninushi: JAPANESE DEITY in Encyclopaedia Britannica [online]. (Accessed: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Okuninushi)

5 November 2009. Yonaguni, Japan in New Scientist [online] (Accessed: https://web.archive.org/web/20091128015636/http://www.newscientist.com/article/mg20427361.500-yonaguni-japan.html)

Walton, D. 2017. Who Built the Fascinating Ñaupa Iglesia? Mysterious Ruins in the Sacred Valley of Peru in Ancient Origins (online). Available: <https://www.ancient-origins.net/ancient-places-americas/who-built-fascinating-aupa-iglesia-mysterious-ruins-sacred-valley-peru-021345>

Glascock & Kuzmin, 2007, Pp. 99-120.

Borić, 2002, p.1030.

Soderman, NASA; Macey, 1994, p. 75.

National Ocean Service, 2005.