Spheres of (Artificial) Influence: Stacking the Biosphere-Noosphere-Technosphere

The Expanse | Part 8

“The only way of discovering the limits of the possible is to venture a little way past them into the impossible.”

- Arthur C. Clarke’s “Second Law”, 1962, P.21

Stacking Spheres

As Benjamin Bratton puts it in his influential technological thesis “the Stack”: “there is no geography without first topology… no nomos without topos”.1 An ode to ontic structural realism (OSR), past and present observations have suggested “rules” (nomos) emerge out of the connections and relations between points in “space” (topos). Discussed mostly in hushed, mahogany-stained, ontological contexts. Like OSR on TRT,2 Bratton goes on to outline how our entire computational megastructure (what he labels “the Stack”3) is at once a planetary-scale infrastructure, connecting people and geographic locations once disparate, and a completely new architecture, informing the division of Earth into “sovereign spaces” at unheralded rates.4 Structurally, “the Stack” is formidable. With a foundation entrenched deep into the planet, where rare-Earth minerals and raw energy sources are tapped and extracted, swathes of space encircled and expunged, duly supplied to the “resource-management” and “chip-development” layers of the megastructure before being fed into the collective nodes of the wider global network, passed on into the “cloud” and, from there, “interfaced” with users (human or non-human), citizens, who perhaps now more appropriately should be labelled netizens. Standing in the shadow, looking up and following the towering mass of “the Stack” before us down to its root source suggests that, at present, the technosphere is completely dependent on the biosphere for maintenance, expansion, and ultimately survival.

Yet, the global technology stack did not simply arise out of a puff of smoke in thin air. On multiple occasions Bratton refers to the megastructure as “accidental”.5 Although, having said that, a puff of smoke is not too far from the truth. Since mass industrialisation fed into mass computation (fumes aplenty), various spheres of influence have morphed around our needs and our vices, becoming intermeshed, the scale of potential and actualised impact increasing proportionally to the mass of “the Stack” over time. In other words, the technosphere becomes a substrate from which new objects, organisations, entities, grow from. Ecologically analogous to a distributed mycorrhizal network which many, smaller and distinct mycelium networks interconnent with, structure completely below the surface, until up rises a fungus, a single, in some cases delicately, dangerously, and massively complex manifestation of the information processing happening within the wider distributed network. Unlike the pile of fungi, however, “the Stack” is an artificially-enhanced information processing system, and is thus more prone to asymmetries and more consequential failures. It is, after all, highly anthropocentric. From “here arises the problem of the reconstruction of the biosphere in the interests of freely thinking humanity as a single totality.”6 Anthropocentrism—the imprinting of our species onto the environment—enacted more and more through technology, is reaching a climax. As pioneering visionary Vladimir Vernadsky put it back in 1945: “This new state of the biosphere, which we approach without our noticing it, is the noosphere.”7

“The Stack” in all its layered and intermeshed glory (Source: Bratton, 2015, P.66)

What an incredible visual of the hominid tech timeline (Source: Max Rosa via Our World In Data)

Some may argue that without mind there is no technology. There are many interpretations of what philosopher Martin Heidegger truly implied when he said, “the essence of technology is by no means anything technological.”8 In an idealist sense, the essence of everything is mind. With “noos” being Greek for “mind”, one potential reading of “The Question Concerning Technology” may be bolstered by thinking about the “noosphere”. Julian Huxley, introducing Pierre Teilhard de Chardin’s 1965 work, “On the Phenomenon of Man”, succinctly described the noosphere as the “web of living thought”.9 Intuitively, then, it is easy to recognise the structural neccessity for an intermediary sphere of human thought to exist before such a phenomena as the exponential stacking and expansion of worldwide technology begins to take place. Without our version of cognition it is not clear that technology would exist at all. Could this have been Heidegger’s elusive “essence”? A steady iteration of hominid inventions, from fire-making around 1 million years ago and agriculture at the end of our last Ice Age, to modern communications and information technologies in the past century alone, standing at the apex, wind in our hair, for the first time in recorded history the hominin species, operating within this particular envelope of collective thinking, “becomes a large-scale geological force.”10 What is accomplished with this force? Harvesting the biosphere to convert raw materials into ever more ambitious and industrious constructions and inventions, “with some parts arising here and then spreading there, other parts elsewhere, with interconnections and interactions increasing over time, until the entire planet would be caught up in webs of creation and fusion.”11 The resulting hive of activity produces the multitude of parts necessary to keep the technosphere alive. Like a strong cognitive glue, the “noosphere” keeps the entire “the Stack” from toppling over through sheer force of mind, and a little bit of old fashioned bruteforce. How long can this be sustained is another question entirely.

However, the substance of the noosphere is largely intangible.12 Starting within the limits of the possible, then, if the “biosphere” represents the space in which “living matter is concentrated in a thin but more or less continuous film on the surface of land in the troposphere, in the forests and fields, and permeates the whole ocean”, then the “noosphere” becomes the even thinner slither of “mind” (noos), layered atop this natural (physis) sphere (sphaira). Given thinking, or more generally “cognition”, is one elemental property of the noosphere, using the conventional definition of the “biosphere” as the sum total of organic matter on Earth, the “technosphere” becomes the sum total “Stack” of technology within the biosphere, and the “noosphere” is thus the sum total of human thought within the biosphere, expressed partially through technosphere. From here it is clear the technosphere “grows out of” the biosphere in the sense that organic matter (e.g. natural gas) is transformed into energy to continuously grow “the Stack” (e.g. power grids). In the sense that human thought is the primary driver behind these technological leaps, it is also suggested that the technosphere equally “grows out of” the noosphere. In some sense self-perpetuating, the noosphere, whilst iterated onwards by the technosphere in a reciprocal feedback loop (e.g. new thinking leads to new communication technology which leads to the coupling of diverse minds which leads to new thinking etc), also exists partially nested within the technosphere itself (e.g. new thinking leads to new artificial intelligence (AI) systems which leads to new data analysis which leads to new thinking which leads to new AI systems). This comes down to the connective medium of interfacing.

Interfaces are thresholds. They connect and disconnect in equal measure, structuring flows by combining and segmenting it, enabling it or frustrating it, bridging unlike forms over vast distances and subdividing that which would otherwise congeal on its own.13

Both the technosphere and the noosphere act as interfaces. Whereas the technosphere serves as software (e.g. programmes), hardware (e.g. microprocessors), and interface (e.g. enabling a physical system to enact change in non-physical space), the noosphere acts like a software (e.g. cognitive function to think of a rocket), hardware (e.g. the mechanical or bioanatomical components necessary to move and create) and an interface (e.g. actually making a rocket engine “appear” through both the biosphere and the technosphere). The noosphere provides a means for forms in non-physical space to manifest themselves in the physical world. A bit like morphospace in anatomical creation, only the noosphere generates technological forms and objects instead. An interface through which the technosphere can “engage” the biosphere. Our species, our thinking, is the conduit. However, as was shown by the second example above, if the tech stack, especially new AI systems, keep evolving to the point where there is less and less of a need for the noosphere (or, specifically, the human mind) to act as the interface between the biosphere and the technosphere, not only is the technosphere growing within the biosphere, and expanding contiguously with it, soon it may not even need the human mind to interface with the natural environment.

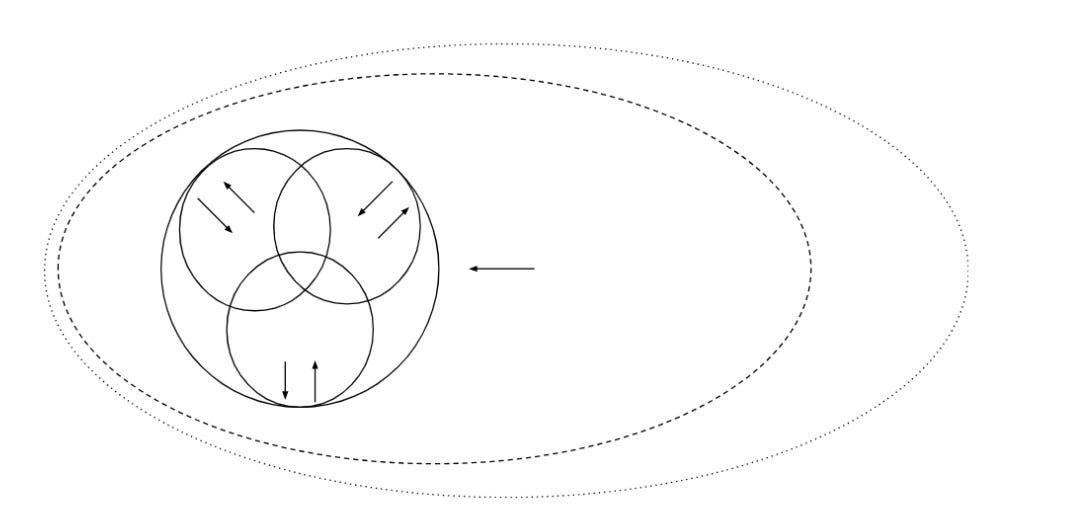

In the spirit of stacking, we can imagine the spheres of influence mentioned thus far:

Under a different context, I have previously sub-defined the “biosphere” as “the natural environment of a particular geographic location”. Dovetailing with Bratton’s framework of “topos” (space or location), the technosphere becomes “the digital environment of a particular artificial and geographic location”. Following this line of reasoning, the noosphere becomes “the cognitive territory of a particular artificial and geographic location”. As above, these spheres of influence are “stacked” in order of recency of impact (e.g. the technosphere is at the top of the stack because it has only risen to the point it is at today within the past century, give or take), and they are also “nested” in the sense that the “inner sphere” evolves within, then through, the sphere or spheres, external to it, and is thus tightly coupled with, and dependent on, any outer spheres of influence (e.g. the noosphere could not exist in its current form without the biosphere, which could not exist in its current form without the magnetosphere—see visual below).

Sticking with a more spatially real ecological perspective, the notion of geographical determinism focuses on how topographical features within the shape of the landscape itself can have a direct influence on the development of living and inert systems inhabiting that space. When it comes to technological determinism, which, “simply put, is the idea that technology has important effects on our lives”14, it becomes clear there is a critically “dual” route along which “the Stack” can influence our lives:

(i) the artificial network topology and (ii) the geographic topography.

Whilst it seems subtle, this dual nature permits “blending” of spaces, and merging of spheres of influence, at an increasing rate. Later in this article series this property will become a key point of interest for thinking about how the digital and physical spaces are merging. For now, studies into the “techno-bio-politics of life… shows that the contemporary government of life is not primarily concerned with life itself in its biological re-constitution but rather with life as it is interfaced with and through technology”.15 When “blending natural and artificial information into composite manipulative substances and habitats, one question to raise, after Serres’s parable, is, “What happens to the hand and its universal flexibility to manipulate the world?””16

Technology is at once a revolution, a frontier, and a very mysterious, very consequential, highly dangerous ecosystem. An expanse in all directions. Both natural and digital landscapes, ecosystems and ecologies play a keystone role in how the technosphere develops within the spaces permitted by our planetary boundaries (e.g. it is difficult to spread robust, non-destructive, yet reliable technological infrastructure to people inhabiting the Amazon Rainforest, given the climate, the terrain, and the ecologies, yet with new satellite communication technologies like Star Link, infrastructure, and with it information flow, is starting to reach those previously inaccessible areas, with mixed consquences as a healthy equilibrium is yet to be found). But what is even more subtle than a satellite thousands of feet in the air is how technology develops as if it without the need for physical space either. Yes, the technosphere is dependent on energy from the biosphere, but the negative externalities of energy and resource extraction required by the “sum total tech stack” subsumes those very same natural spaces it relies on, and in some cases completely removes them from existence. Thus, even though the technosphere is dependent on the biosphere, it does not inherently make the relationship symbiotic. What’s more, given the ability for the “the Stack” to grow in a space paradoxically “internal” to yet “distinct” from the biosphere, it begs the question:

To what extent will we begin to replace the physical topography of our landscapes with the non-physical topology of the digiscape?

Spatial Realism across Spheres of Influence

Thinking about the biosphere and technosphere leads us to a perspective of spatial realism, placing, as Bratton did, the “topos” (space) as a fundamental prerequisite for the emergence of “nomos” (rules). Regarding rules, mathematician Stephen Wolfram has pointed out that “There are lots of analogies between physical space” and other, abstract but very real “branchial space, and rulial space.”17 In Wolfram’s estimation rulial and branchial space corresponds to every possible underlying rule, and the “ruliad contains everything that is computationally possible.”18 In mapping, more specifically, graphing these topological points of interest, the terrain laid out by Wolfram’s “Physics Project”, he says, may well present a unified theory regarding fundamental fields (including consciousness, general relativity and quantum mechanics) that remain fatally incompatible to this day. Regardless of whether or not you place any hard ontological truth in the ruliad, the point remains simply as a heuristic to think about how, as “the Stack” continues to compound on itself, the rules, the relations between points in space and objects evolving as a part of this environment that branches the non-physical and physical, exist as a fundamental part of the technosphere. When built from complex topological structure, it seems to logically follow that equally complex, self-adapting relations, processes and feedback systems will be native to that space as well. The biosphere and planetary system as a whole is a great example of this. As more rules transition to, and appear uniquely from, the technosphere, they will exist in a dual nature, at once within and without the reality we are most comfortable with: the chirping of the birds, the Sun on the back of our necks, the laughter amongst the humanity.

It is clear the biosphere is not just the space of living systems and inert biological matter, but it also represents the geo-physical space that human-dominant, anthropocentric spheres of influence (anthrospheres) like the sociosphere, politsphere and technosphere, all emerge from. Spheres compacted with interrelations, rules, and interdependencies, fields of human thought and actualisation that sprout complex and powerful “entities” (e.g. states, Gods, networks, egregores, hyper-agents), spaces as equally interconnected to the larger “primary” planetary systems like the geosphere, hydrosphere, atmosphere, and (geo)magnetosphere. With regard to human life, however, through which we all create, engage and experience reality, without the biosphere no meaningful anthrospheres could exist. And that is important, namely because Life is what makes Earth Earth.

Our little bubble of air, buckets full of deep blue, green space, land to grow, what ever shall we do.

Visual aid for imagining the “anthrospheres”: the sociosphere, the politsphere, and the technosphere, all encapsulated within the biosphere, nested together with hydrosphere, geosphere, atmosphere and within larger planetary systems like the magnetosphere.

Life, in all facets, occupies certain “spaces” around us. Life can be broken down into living systems, and the biosphere used as a set to classify the space of living systems. Naturally we assume living systems will occupy the space of the biosphere into the future because that is what paleontological, archaeological, geochemical, and other modes of evidence suggest have happened in the past. Objects have become living systems, and in some capacity have occupied the space, albeit hidden in obscure, absurd niches. Two facets: (i) human life, and (ii) non-human life, range from occupying distinct regions to very close, sometimes even the same, space (think about our relationship to microbial organisms, or that of a tick to an elephant, moss to a tree).

Throughout this series the focus has been on “objects” in “space”; because we are studying the interrelations between the biosphere and the technosphere, if we were to collapse “living” and “inert” matter together, what we are left with is simply the premise that, over time, “objects” assemble within the many niches of Earth—without needing the noosphere of human cognition. Whereas Vernadsky posited that “the objects of study in the biosphere are to be regarded as the natural bodies of the biosphere”,19 the mass of “the Stack” indicates that when we “extend the traced path for modern interfaculty from objects as primordial interfaces, shifting then to graphical signs as modern interfaces, and again back to objects, now imbued with the computational intelligence to interpret our gestures”,20 the objects that stare back at us might not be too intuitive. Neither may their spheres of influence be either.

Albert Einstein not only curved space but he also assured us it has an inherent expansive quality to it.21 Spheres of influence, following the most fundamental spatial dynamics, continue to expand and interplay with one another. Postmodern social, political and ecological systems are all beginning to merge. Spatially, and visually, we see encroachment of spaces when we notice the “rewilding” of urban settlements, or, inversely, the eroding boundary between dense natural ecosystems and dense anthropocentric social systems. Of course our ancestors lived in many ways “merged” or “converged” with the land, but this was in a much more hands-on way, living with and off the land. Birth rates were hovering around 0.4% between 10,000 BCE — 1700 CE. By 1963 they had increased almost six fold to 2.3%. With public infrastructure and construction of “brick and mortar” buildings such a mainstay, clearly anthrospheres delineate themselves somewhat from the ecological world. When the steady advancements of technology are factored in, this expansion of humans into non-human space, and vice-versa, only increases congruently.

Manaus: Amazon Rainforest meets the City: the ecological and anthropocentric systems merge. (Source: Jordan & Howard, 2020 via Greenpeace)under the impending bio-techno convergence “objects” can range from mountains and trees to skyscrapers and aeroplanes, to pebbles on the beach to computer chips sitting in a factory, from dolphins and coral reefs to humans and elephants—all woven together into the objective living and non-living occupation of space.

But, as it stands, it is evident objects also exist outside of immediate anthropocentric or even biospherical space. Astronomically speaking, estimates attribute a high probability to there being up to two trillion galaxies in our observable universe alone. Galaxies are considered objects, simply collections of smaller solar systems, interstellar dust and gas, held together by gravitational forces and the shape of space. Galaxies exist nested within larger objects, galactic clusters, walls and sheets, themselves part of the filaments and voids of the larger cosmic web. Our universe itself may not be n of 1. Zooming back down, objects exist around us, in us (e.g. stomach obelisks), through us (e.g. in the case of neutrinos, over 400 billion each second), in non-physical mathematical space, even meta-physical Platonic Space, and, to be honest, at this point, it seems to me that objects exist in pretty much every conceivable space. Object-Oriented Ontologists (OOO’s) would say this is because objects are fundamentally autonomous and as ontologically true to reality than the very structural relations allowing them to exist. Those in “Camp OSR” would disagree. Idealists might say this is all in our heads. In all honesty, OOO knows? (Sorry.)

Whatever way you want to swing it, spatially, it appears as objects—being a collection of constituent parts to make a whole— appear in spaces across a universal scale. That is not the contentious part. What is is the classification of the “complexity” of these objects. How quickly, for example, do environmental, and for lack of a better term, “evolutionary” pressures effect change that object, even promote an adaptive response? How long ago did adaptive behaviour become hard problem solving? Until parts can compound on parts and stack themselves into ever more intricate sets of nested architecture? Rebuilding the distinction between “living” and “inert” matter collapsed earlier, in the case of organic Life—if you believe that fundamental cellular and even molecular systems constitute hard problem solving tendencies—significant change to living-object complexity was affected billions of years ago.

So, in the case of the biosphere, quasi-complex organisms were “assembled” billions of years ago. It has taken the biosphere around 300,000 years (thereabouts) to incubate human cognition to the reach the point of the noosphere we, as a collective, stand before now. From the manufacture of the first integrated circuit board in 1959 to where the peak of “the Stack” reaches now, as of July, 2025, it has taken the noosphere around 60 years to produce some of the most complex, non-physical and physical technological objects ever known to history. Thus, if wishing to observe an “assembly space in action”, a production line where sparks are flying out hotter and faster than a jail-broken plasma-welding GPT, one has to look no further than the technosphere.

Boundary Conditions

But let us take a step back and zoom out for a second. So far we have focussed primarily on the interrelations between the biosphere, the technosphere and the noosphere. That is because these spheres of influence are clearly in a current state of convergence and merging, and provide obvious value to the overall goal of looking for artificial lifeforms evolving from what we have been calling “the Stack”. But please permit me a short digression; when we are talking about what appears to be fundamental object development across spatial dimensions, let’s say, from organism-up, it helps to map the various “higher and lower” scales of influence and causal chains, in order to get a more broader perspective on object evolution in space. In a 2D sense, to get a feel for the spatial structure without getting lost in the weeds of abstraction, I imagine something like:

Which is then extended to:

Nested doll— systems within systems:

((S:sociosphere(P:politsphere(T:technosphere((B:biosphere(H:hydrosphere(G:geosphere(A:atmosphere(M:magnetosphere((Pn:planet((Sol:solarsystem(Gal:galaxy(CW:cosmicweb(U:universe)((OU:outer-universe)((?))

Nested Circle Model

From this simple combination of letters, circles, and arrows we can scaffold our way towards some further insight. Besides, was it not Pythagroas who said that “there is music in the spacing of the spheres…”? What now may be thought of as active patterns of agency across various scales of spatial structure.

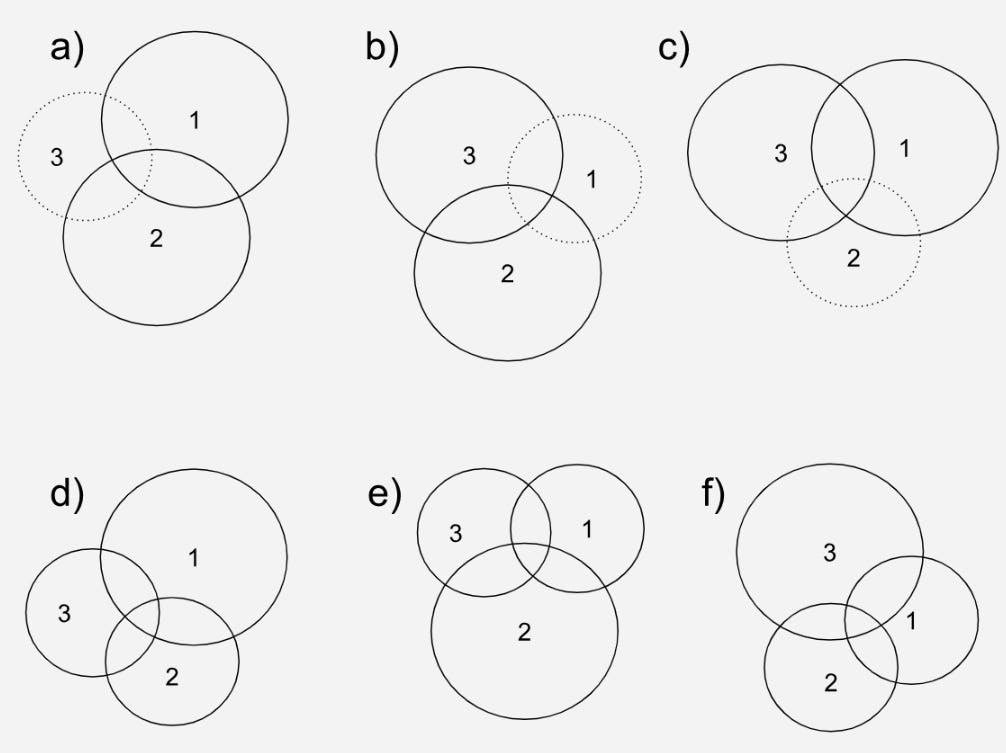

Another way of interpreting this set of nested circles is by noticing the interconnection of each individual triplet at the centre of this map. Just like how movement in one Borromean Ring affects the rest, each of these spaces act upon one another in a unique way. Interaction based on what object, mass, system, agent, organism that is generating movement within each space (e.g. the fault-based systems within the geosphere actualises its potential, causing an earthquake, in turn affecting living systems, masses, entities and agents inhabiting the biosphere). If you have ever read or watched “The Three Body Problem”, you might come to a quick realisation three intertwined spheres present a pretty tricky set of potential behaviours and influences, especially when these are anthrospheres.

Basic asymmetrical spatial dynamics of three “game theoretic Borromean Rings”:

a) spheres 1 and sphere 2 extract from sphere 3; b) 2 + 3 > 1; c) 1 + 3 > 2; d) sphere 1 extracts from sphere 2 and sphere 3; e) 2 > 1, 3; f) 3 > 1, 2.

When you then assign sphere 1—socioeconsphere, sphere 2—politsphere, and sphere 3—technosphere, the shifts in dynamics becomes less mundane, far more confusing and when war and conflict dynamics are factored in, potentially catastrophic.

What is the metaphorical driving “force”, the “essence” that Heidegger looked to get at behind technology, that which Pythagoras heard behind each sphere? I like to imagine the biosphere powered by living organisms and scale-invariant planetary systems akin to Lovelock’s “Gaia System”. Whereas the sociosphere runs off human connection and associated structures, I would argue that the politsphere is fueled by Games of Power and personal ambition, some that betters the “principals” (citizens), others that better the “agents” (politicians). Embedded into both, the technosphere appears to be governed by exponential advancements in information and materials technology, using tremendous resource extraction across all other spheres in order to expand. What was once a by-product of our noos is now the topos encapsulating us.

As indicated by arrow direction, the smaller inner-spheres (the techno, socio and political) can act upon the outer-sphere(s) encompassing it (e.g. the technosphere polluting the atmosphere), and this larger sphere can in turn act on the smaller ones nestled inside of it (e.g. the atmosphere “washing” away parts of the sociosphere during severe flooding). Thus, one quick way to think about these interactions is by looking at how one sphere affects another, through things like structures, feedback mechanisms, objects, actions and causal relations. In a multi-scaled sense, the smaller, nested inner-spheres increase entropy from the larger, “host” outer-sphere. Akin to how the Karl Friston’s “Free Energy Principle” has been applied to James Lovelock’s “Gaia” model of Earth-systems, including the engagement of living systems within it. Further, technosphere is a pertinent example of how entropy from the larger system is extracted and transferred to implement growth (beyond mere equilibrium) in the inter-nested smaller systems.

On one hand this can be viewed as problematic when the larger system is a finite biosphere (meaning it does not contain, as far we know, unlimited resources to continue fueling the smaller systems needs forever), as this suggests an eventual “draining” of energy “out → in”, by the smaller nested spheres.22 Daring, however brief, to follow the causal structure outside of the biosphere we enter the oblong shape of the unisphere. For now the causal direction remains one way only: from the “top-down”, that is the unisphere affects the biosphere and not vice versa.

If we zoom back in and look at the highly interconnected inner triple Venn rings, we may see how “information and communication technologies have manufactured and re-configured the techno-social fabric of how we live” and “that life has increasingly become manufactured or, as we would like to call it, ever more intimately interfaced with and through technology.”23 Social scientists are here pointing to the mergence of two spaces in particular, the sociosphere and the technosphere, to the point of re-configuring the structure of the techno-social topos and nomos. In many ways, when we watch the daily news cycle it is hard to not feel as if the technosphere and politsphere are extracting from the sociosphere in some not-so-insignificant way. If technology itself is a hyper-object, a massive relational structure outside of our regular notions of space and time, (as if a pencil pushed into the back of a piece of fabric, of which from the front we only see the distorted form the fabric takes, not the object itself) and politics the space of powerful groups and organisations wielding technology to maintain control, stability, moreover influence, as Bratton alludes to throughout his work, a computational future seems inevitable; the best we can do it try and manage it as effectively and synergistically as possible. I am not saying give in to AI Overlords, I am saying, like any optimal merging of spaces which our current situation presents, the best outcome is one that looks for actionable methods around using the technosphere as a tool for net-positivity. That being said, when in my workshop, if I have trained you on a tool, and you are using said tool, you best believe that it is now as much your responsibility as mine—I will do my best to look out for you, but when my back is turned, if I have done my job properly, you will know how to handle that tool so that you do not hurt yourself, others around you, and ultimately you are able to produce the desired outcome, like a beautifully crafted dovetail joint. Being born into the shadow of “the Stack” has its pros and cons, but technological potential is equally beautiful if crafted, and implemented at scale, net-positively. Easier said than done. Yes, I am optimistic. But I also fluctuate steadily between realist and idealist. Certainly a little romanticist, strifed with an occasional bout of existentialism. So is the complexity of the human mind, of noos, of the thinking substance. What such a blending of spheres could mean for the sovereignty of biological life in the coming decades, for mind, is anyone’s guess.

We know physical life rests in complex structures like DNA and RNA, or the molecular chains that compose natural protein-machinery. Social life rests upon the physical infrastructure built up and around groups of people. Political life is held together by governance institutions new and old. The epitome of technological life may be the sum of algorithms and the collection of machines keeping it all running, but “the Stack” suggests there is more at play, and vastly more at stake.

Certainly a quick glance around a commuter-packed train seems to suggest that, on average, we do not own technology; quite the opposite: technology owns us. Our personal tech stack rules our life as much as any other sphere of influence. Not wanting to forget the wisdom of there is no nomos without topos, it is more essential than ever we know just what sphere of influence we are being pulled into, or already under. The biosphere gave rise to the noosphere, and the noosphere very quickly gave rise to the technosphere. This had led some to ponder whether or not technology as a “phenomenon” has always existed in some innate capacity, sitting in the causal structure of Platonic Space like a hyper-object awaiting an agential intelligence to form, recognise it, pick it out and put to use.24 But the technosphere is now giving rise to new facets of the noosphere. It has turned around and began optimising and re-designing what it means to “think”, what it means for “intelligence” to exist. In the same way how objective assembly spaces exist outside of our control, the technosphere exists not only dependent on the biosphere, but is now self-assembling the components needed to become independent from most, if not all of us, evolving on its own, at an ever-increasing rate, providing the answers it needs to adapt to new environmental niches to maintain survival as it goes. In Chardinian terms, hereditarily speaking, the technosphere is simply an exercise in compounding intelligences. It started with human intelligence. Where it ends appears to be artificial. Have the biosphere and technosphere been merged from the first whsipers of the noosphere, whenever that may be? Reframing our perspective on our such a bio-technocentric relationship:

Technology is not something happening through us, it is something happening to us.

Returning to an ecological analogy, ecosystems exist in our biosphere as networks of food webs and hierarchies of predator-prey relationships all intermeshed into large, constantly changing systems. “Eco-systems consist of groups that are comprised of organisms, which in turn are made of organs composed of tissues, which consist of cells made up of biochemical networks.”25 But in a multiscaled nest of systems, new ecosystems are emerging, not in our biosphere but in our technosphere. A cybergenesis many still believe is separate to the space they inhibit. Yet experts see a “fast-paced and resilient industrial internet of things (IIoT) ecosystem” rapidly evolving, one which “creates a sustainable nexus between social, economic, and environmental aspects.” The bottom line is, those who have their heads deep in the technosphere are discussing ecosystems evolving not only within physical spaces (like the sociosphere and the natural environment) but developing further in other spaces that are “non-physical”. The technosphere brings with it non-physical ecologies with the power to greatly change the physical world around them.

Having grown up glued to the TV whenever the soothing tones of Sir David Attenborough appeared through the screen, in my mind, the concept of ecosystems is tightly coupled with the concept of organisms operating in that space. It is difficult to imagine one without the other. Artificial organisms, it seems, are approaching.

Testosterone Replacement Therapy

Which will be interchangeable with “technology stack” or “tech stack” from here on. Not interchangeable with “obelisk”, although hearing “the Stack” does induce something between a HP Lovecraft Martian world and Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Gabriele de Seta, 2021, Gateways, Sieves, and Domes: On the Infrastructural Topology of the Chinese Stack, P. 7.

e.g. Bratton, 2015, P. 61.

Martin Heidegger, 1954, P.1

The RAND Corporation, 2020, Whose Story Wins: Rise of the Noosphere, Noopolitik, and Information-Age Statecraft, P. 7.

The RAND Corporation, 2020, Whose Story Wins: Rise of the Noosphere, Noopolitik, and Information-Age Statecraft, Pp. 10-11.

Although Pierre Chardin did partition the concept into three distinct components:

(i) “hereditary”—meaning the compounding nature of genetics, information, knowledge, wisdom, behaviours, actions, decisions, are all based on those that came before, not quite unlike the “Mimetic Theory” of Rene Girard.

(ii) “mechanical”—the ability to use machines to further our output in every sense, energy extraction, communication, information processing, whilst Chardin wrote this at a time where computation was in its infancy, he imagined the use of radio and telecommunications to propagate the global formation of the noosphere.

(iii) “cerebreal”—this to me is the “essence” of the noosphere: the ability to think, to imprint oneself on the environment, to embody agency, to manipulate and generate objects, to write prose, poetry, compose ensembles, enact plays, strategise, rationalise, abstract, achieve, dream, and ponder, to invent, map, listen, sense, observe, record, interpret, participate and ultimately experience the world around us in this fundamentally unique way.

Bratton, P. 228.

Adler, 2001, P. 1.

Bratton, 2015, P. 227.

Stephen Wolfram, 2020 - the “rulial” space will be discussed in more detail later in Keepers of the Expanse.

Bratton, P. 227.

Giles Sparrow, 2018, What Shape Is Space?

Of course, the first law of thermodynamics affirms the “eternal” nature of energy, stating that it cannot be created or destroyed, only transformed from one form to another, and consequently, the total energy remains constant, merely existing in different states. That being said, the “transition” from “state” to “state” can have massive implications for the physical space whose energy is being “transformed”.

Here I am adapting the interpretation of Heidegger’s “A question concerning technology” as put forward by James Madden, 2024, Unidentified Flying Hyperobject: UFOs, Philosophy, and the End of the World.

Michael Levin, 2019, The Computational Boundary of a “Self”: Developmental Bioelectricity Drives Multicellularity and Scale-Free Cognition