From the get go, just so we are on the same page, I feel obliged to tell you that I am a little suspicious of fault lines. Aside from giving them a cursory side-eye as I walk on by, I am not a complete pessimist. Of course, not everything is their fault. But this is all besides the point. What I am getting at here is that fault lines may have a lot more to do with our fundamental human experience than we give them credit for. And wait, I know what you are thinking: earthquakes…

Indeed, seismic activity is one major contributor to our human experience. At some point, however, we will need to try and move past the well-documented, destructive physical effects like all the ground-shaking, building-collapsing, power-grids-outing, landslide-cascading, tsunami-crashing. Events such as these no doubt shape our human experience on a fundamental level, irreversibly changing the ever-branching course of history for ever, unsanctimoniously shoving us in the back one epoch to the next. Yet, as always, there may be more hidden just below the cracked surface, more within the streams of causal relationships flowing between tectonic layers and the conscious human experience. It is that something - those faults - we try to uncover here.

Seismically Dense

Disclaimer: If you are already familiar with the inner-workings of seismic activity and the general notion of fault zones then feel free to skip this part and head straight to Part 1.2 - Correlation vs Causation: Don’t Shoot the Messenger (released concurrently).

That is where things start to get weird.

“To the Circle of Fire; those who have gone before, those who are present, and those who have yet to come.”

- Miguel Ruiz

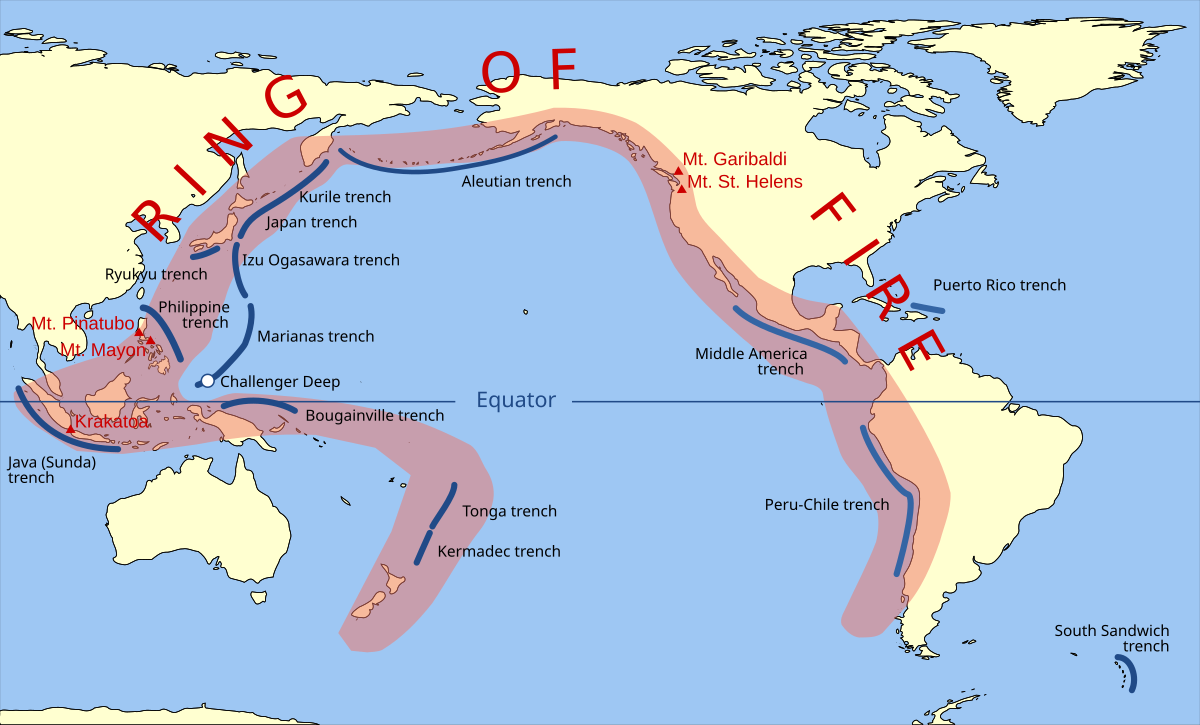

Coming to Terms

A certain phrase is known to strike fear in the hearts of many. Have a little peek at the map above and follow this route: starting at mountainous peaks of Te Waipounamu - the South Island of New Zealand - stretching north-east until you hit the remote chains of Pacific Islands, then changing course due west, past the luscious growth of Papua New Guinea and further west still across the Greater Sunda Islands of Indonesia, Bali, and Java, then turn north, past the serene Philippines, flowing further up still across the heart of the Japanese Archipelago, before fanning out east along the barren southern coast of Siberia, trudging on across the Aleutian trench, bridging Alaska and fighting off frost bite until you eventually hit the West Coast of the United States where you continue down, past Mexico, ignoring the gentle coo’s of temptation from the sun loungers and margaritas, through the narrow corridor of Mesoamerica and opening up to traverse the expanse of the South American coastal zones of Peru, until finally coming to a grinding halt off the deserted coasts of southern Chile. If you followed, fair enough - that was quite long. All along that enchanting horseshoe shape you have just traced exist zones of intense seismic density - fault lines. Collectively these seismic schisms are known as the “Ring of Fire” - that dreaded phrase.1

Perhaps I have got a little bit too far ahead of myself here. Let’s rewind a little. Fault lines are fractures within the Earth’s crust, ranging in length and depth from a few millimetres to hundreds of kilometres. Given the Earth's geological assembly, the rock on either side of these fractures tends to move on a scale so immense that for most of our history we have attributed it to the will of the Gods. Tectonic movement can take seconds, producing sudden earthquakes, or it can slowly grind away over hundreds of millions of years, as is the case with orogenesis - mountain building.

Try something for me: bring your two fists together so that the knuckles slot neatly into one another. The wavy line made by your connected knuckles represents where Earth’s tectonic plates meet - the fault line. Your two fists are the opposing tectonic plates. These plates divide up the mostly solid outer layer of our Earth - the lithosphere. Now imagine your fists are resting on an overflowing bowl of jelly. These solid tectonic plates - your fists - sit atop and move along this soft inner layer. The asthenosphere - a semi-liquid layer of molten rock stuffed within the big jam donut that is Earth, sits around 100 to 250 km below our feet. Two parts of the overall planetary tectonic system, the lithosphere and the asthenosphere produce three key movements:

“convergence” - pushing together - forming mountains, volcanoes, and deep ocean trenches

“divergence” - pulling away - creating rift valleys and mid-ocean ridges

“transformation” - sliding past each other horizontally - producing fault valleys

Different types of plates influence different types of movement based on different types of variables (i.e. where the plate is located spatially on our planet, its dimensions, or its history of activity) and each type of plate produces novel features and processes localised to its fault zone (such as geological and ecological niches). Below is a major fault line map of the world.

On the maps above we see the major fault lines run along the intersection of tectonic plates. However, fault lines do not just appear where plates collide or separate, they also appear running throughout the breadth of tectonic plates. Some of these intraplate fault lines cause new fractures to snake into the surrounding rock, becoming future plate boundaries if they continue to increase in size and scale over geological epochs.

In the meantime, any stress that builds up along any of these fault lines, large or small, young or old, is finally released and the ensuing aftershocks of seismic activity ripple out into the surrounding space. Again, the brevity of this release depends on a number of factors (e.g. type of plate boundary, geographic location, past history of activity). But, considering there can sometimes be over 50-80 earthquakes every single day - upwards of 20,000 each year2 - it makes logical sense that intense seismic activity is what we all think of when we think of fault lines. Earthquakes certainly deserve respect, and need hearing out.

Seismic Impact

Beauty is a hell of a thing. Mesmerising; hard hitting. True there can be beauty in danger, but those who find themselves amongst dangerous beauty often pay a heavy price. Having a look at the previous maps, it becomes apparent that the landscapes within fault zones often include some very astounding geological and ecological features.

Between the US and Mexico four major faults and seismic zones crack their way across the subterranean land. The San Andreas Fault, a transform boundary between the Pacific Plate and the North American Plate, is characterised by strike-slip faulting. Down below strike-slips cause one tectonic block to move left or right relative to the other. On the surface we feel the movement through devastating occurrences like the 8.1 magnitude earthquake that tore through Mexico on September 19, 1985, causing the death of thousands and untold destruction to private property and public infrastructure. Tectonic slips out of sight below still demand a heavy price up above.

Further south in the Americas claxons ring out. Sirens fit for an air raid reverberate through the narrow cobbled streets; a deafening roar fit to induce panic in the most hardened mind.

People are not exactly panicking, but they do file out of buildings, hide under tables and take shelter in neighbouring doorways. Yet to feel the Earth flinch nor the buildings rattle they wait, anticipation and heart rates rising in a steady crescendo through the quieting din. The Peruvian people sit at the flaming heart of it all. With the Andes Mountain Range being a feature of a convergent “mountain-former” boundary where the Nazca Plate subducts beneath the South American Plate, numerous, intensely active reverse faults have long since carved their way through the rocky subsurface. Whilst annual nationwide earthquake drills prevent severe first-degree burns from their position close to the Flaming Ring, somewhat relieved the people of Peru return back to their homes, their work, their families, all the while knowing that next time it may not be a drill.

No drill could have helped prevent the whopping 7.9 Richter Scale earthquake that in 2008 tragically resulted in the death or disappearance of over 79,000 people in China’s southwestern Sichuan Province. Nor could it have anticipated the unfathomable 9.0 magnitude Tohoku Earthquake that took place on March 11, 2011 in Japan, whose cascading catastrophic effects took an unexpected 21st-Century twist in the form of the Fukushima nuclear power plant, into which a 40 metre (shoulder height of the Statue of Liberty) tsunami caused by the underwater quake smashed into and resulted in a nuclear meltdown. Human life and nature paid a heavy price that day. But this is no “one off” for Nippon. Topping out as the most seismically dense location on Earth, Japan’s island chain experiences upwards of 1,500 earthquakes… per year! Truly the definition of “seismically dense”.

Another island chain, situated further down to the left of the flaming ring, experienced nine earthquakes over 6.0 in magnitude in 2018 alone. Thousands of deaths was the unfortunate, but now sadly expected outcome. Whilst the Emerald of the Equator continues to shine bright in the face of adversity, it is often one of the worst hit by suboceanic slips. Claiming almost 12,000 earthquakes in 2018 alone, we only have to cast our minds back to December 26, 2004, where one monstrous tectonic movement caused the Sumatra-Andaman earthquake, resulting in the infamous Boxing Day tsunami, killing over 200,000 people - the majority of damage amassed upon the vibrant, typically dazzling, emerald-ringed beaches of Indonesia.

Whilst we won’t linger on natural disasters for too long, (as they are well-documented and widely discussed), the record of human suffering and the memory of ecological and geological disasters all pose as stark reminders that certain geographic locations can experience things, for the better or the worse, that others cannot. That being said, when we inspect the behaviour of certain fault zones there are a few interesting outliers that deserve attention.

New Zealand, the beginning of our Ring of Fire journey earlier, situated at the lower left-hand edge of the flaming ring, is one such outlier. Don’t get me wrong - the myth-evoking islands are no doubt seismically dense. Often, however, this seismic activity does not just behave in the purely destructive manner we have come to associate with earthquakes. At the crux of this unfelt seismic activity is a process known as “episodic slips and tremors” (EST), caused by the less intense but perhaps equally as influential “slow slip” of tectonic plates. Taking place over much longer periods of time compared to “sudden slips”, most of the time EST events go unfelt by us above ground. While we have other places to visit first, keep these different types of seismic activity close, for they will find themselves at the keystone of speculation in due course.

Now onto some very intringuing correlations, ones that indict fault zones in the underlying causal chains that bind the human experience, for the good, the bad and the downright ugly.

Not just because of the disgustingly brutal college campus drinking game “Ring of Fire” that holds the same name. (If you yourself have never played this game - that is not a bad thing. Perhaps ask your son or your daughter for the rules - I am sure they would be happy to explain them to you.)

Joshi, 2024.