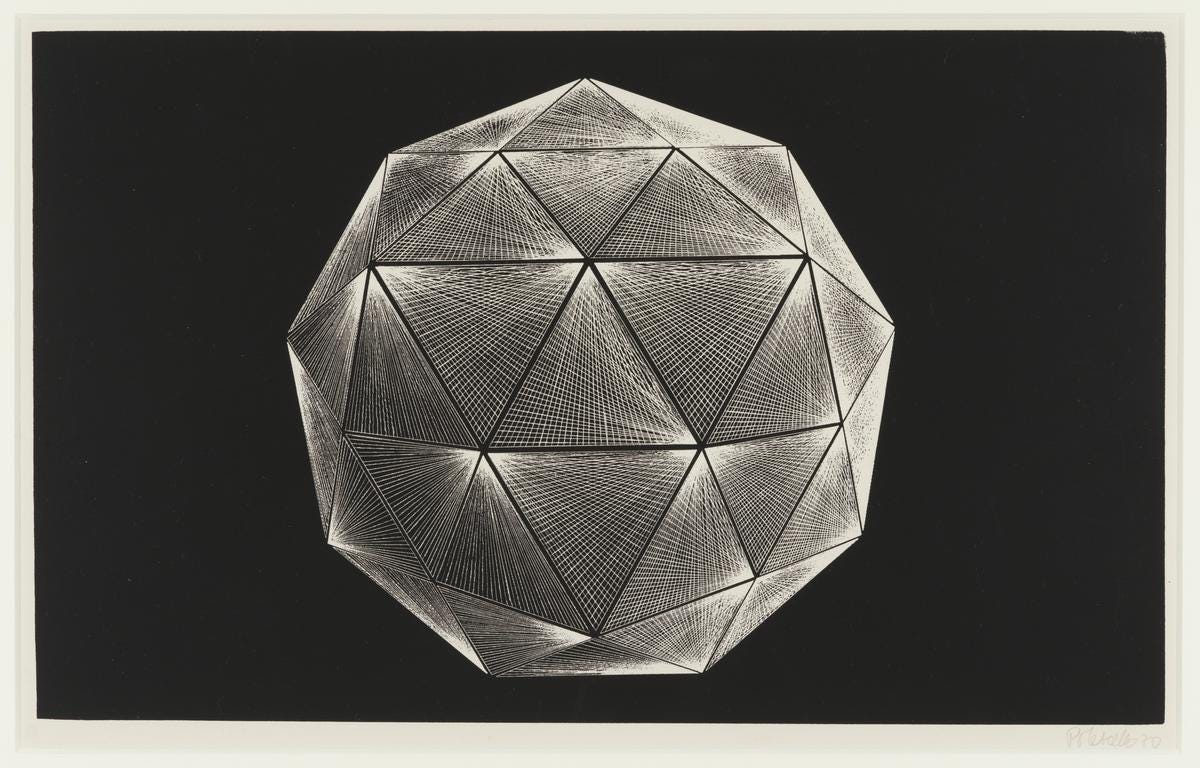

Rogelio Polesello (1939-2014) Untitled 1970 from Media Networks: A view from Buenos Aires: Systems and Communication at the Tate Modern.

Hyper-this, Hyper-that

Okay, so I admit Part 1 was a very long-winded way of saying something needs to have the following characteristics for it to be classified as “social technology” (s.tech):

Ability to directly share a range of media, locally or globally.

Connecting two or more people who can share ideas and abstractions.

Increases capacity to be present with other individuals - be that digitally or physically.

Having seen how s.tech amalgams with the process of hyper-connection and produces, as a second-order effect, phenomena like hyper-sociability (adjacent but distinct from hyper-culture), we should probably look (partially because in my books anything that repeatedly uses the prefix “hyper-” needs to have a chance to defend itself) to define these terms a little further.

Starting upstream, “hyper-connection” is an evolving state where the density, complexity, and speed of interactions between people within and across natural, social, and technological systems are significantly increasing, even when compared to rates of connection only a few decades prior. Three primary characteristics are:

1. Increased Density of Interconnected Nodes.1

2. Complex Cause-and-Effect Chains.2

3. Acceleration of Information Flow and Influence.3

If you take the simple notion that cause and effect webs span existence, from ecosystems to panarchies, from multi-layered cosmic systems to cities and human interactions, then the connection between these cause and effect chains are becoming, in a network theoretic sense, increasingly more dense (more connections in a given space).

Following the compounding effects of modern natural sciences in the era of industrialism, the beginning of the microprocessor technology in the mid-twentieth century, and the post-internet twenty-first century boom of artificiality like AI and quantum computing, more and more links are being added between the nodes of living and artificial systems across our planet.

Travelling downstream, in Part 1 we saw how, hemorrhaging from the social trends emerging at the dawn of Gen Alpha, “global virtual communities” are beginning to replace traditional town halls. As the digital cascades into the physical, glints of what we can call “hyper-sociability” can be characterised by:

1. Global and Virtual Expansion of Social Interactions.4

2. Increased Frequency and Accessibility of Social Engagements.5

3. Replacement of Physical Spaces with Digital Forums.6

Dissecting s.tech by studying the “hyper” nature of both “connection” and “sociability” reflects a profound evolution in how people connect and build communities in the digital age. Communities that are, at least traditionally, encircled by the tight coils of particularly aggressive and powerful entity.

Structural State

The creature staring back at us is the Leviathan.7 But before we jump the gun, with two core concepts associated with s.tech now defined, it is important to see where it all sits in a more zoomed-out world model. One of these world models is based around three structural layers, but more on that one in Part 3. First, it would help to align our imaginations to the kind of global space everything we have discussed thus far exists within. A world model evoking subspaces.8

What we may picture is the entire space of the world’s habitable surface demarcated into separate areas, each subspace governed by a certain group of people. By modern standards, if you were to zoom-in on one of these subspaces and try to define it, what comes into view as the pixels render is - that’s it… got it: The Leviathan!

According to political scientists and forecasters like Max Weber, Francis Fukuyama and John Mearsheimer, humanity exists in a global system of “stateness”. In Weberian terms a “state” equates to a group of people with a legitimate (and effective) monopoly of force/violence in a given geographic territory.9 As we zoom-in to our global spaces the Leviathan hissing back at us is most likely a governance organisation resembling a state of some kind.

Considering there are around 250 somewhat-habitable geographical territories across the world, when we realise 197 of them are one “state” or another, it becomes clear that around 79% of the world's habitable area is covered by some degree of “stateness”. Because states inherently have territory they claim is there's, we can imagine the global space as demarcated into these smaller subspaces, territorially marked by different states (aka groups of people). Even when we layer sociability on top, most of the subspaces in which human organisation takes place do so within the sphere of influence, or at least in the nearby presence of, one state or another.

If we were to zoom into a specific subspace perhaps we would see the standard nation-state (e.g. India, or United States of America), or maybe the standard stateless-nation (e.g. the Basque). We might land on the less standard diaspora-stateless-nation (e.g. the Armenian people). Keep looking.

Whether we see mini-states pop up (e.g. Monaco, or San Marino), or whether we run into cunning states - states “which capitalize on their perceived weakness in order to render themselves unaccountable both to their citizens and to international institutions”10 (e.g. Singapore, or Qatar), there is always a chance we will see some kleptocratic states (e.g. Russia historically, or Equatorial Guinea, or even, perhaps, the United States…).

Certainly we would witness failing states (e.g. Somalia, or Yemen) and it would become hard to miss those hegemonic states - in a model akin to Ray Dalio’s World Ordering thesis: states able to act as economic security for other smaller states in exchange for territory, or other “favours” like resource acquisition or political alignment (e.g. historically and perhaps currently, United States in Western Hemisphere and China in the East).

Stateness, it seems, comes in many shapes and sizes. Moreover stateness, like hyper-connectivity, appears pervasive in our current geopolitical climate.

Bio-Stateness

Stateness can be individual. It can also be collective. Following recent in-roads into the collective intelligence of cells, if we compare collective stateness some interesting analogous material shines through. Membranes separate individual cells, acting like the borders of state subspaces, only within the larger collective biological tissue. Information passes between those individual cell membranes, and the action of one cell can affect the action of other cells. Across the cellular landscape this action even occurs non-locally (and when scaled up, from very far away). If we think of any and all forms of states across the world (most of the habitable space on Earth) we can imagine how, in one sense, collective stateness creates one globalised yet non-unified state system (let’s call this the “GNUSS” for short).11 Stateness, or the GNUSS, becomes the collective geopolitical tissue of our planet.

Like biological systems, the state system begins to decrease in efficiency over time. Structures degrade, information sharing diminishes and the collective tissue begins to atrophy. However, whereas cellular decay only affects one individual and their loved ones, state decay can affect millions.12

Just like cell membranes pass electrical signals from cell to cell to support the goal of information sharing in the wider system, so to do the borders between states. Except, unlike biological systems (the well functioning types, at least), the GNUSS lacks coordination and cohesion at a globalised scale (and more often than not, on the localised scale too). This is one reason for state decay across the GNUSS.13

In both the cellular and the geopolitical landscapes information passes between borders. In stateness, however, this information is collected, stored and “firewalled” by the governing body within that subspace. If an individual cell begins acting like this - essentially shrinking its “cognitive light cone” - then it has become selfish. Cancer is one example of what can happen when cells become disassociated from the collective system.14 States, through their control and manipulation of information passing across and through their borders, also act in a self-interested way. Power games fuel multipolar “races to the bottom”. Nuclear armament, overfishing, lethal drone technology - all dark reminders of this equally dark process.

And let us not forget: just because information passes across state borders, and just because information passes across state subspaces, and just because states collect said information, not all the people inhabiting the space receives it. There are, in some cases, justifiable reasons for this siloing (allowing decentralised nuclear technology to fall into the hands of anyone with an internet connection probably is not the smartest idea).

If, however, you believe that the majority of people are not inherently corrupt and want to do the right thing, then you might argue that one reason we see mass violence, war, nuclear armament etc is because of the power structure provided by stateness. Power corrupts and absolute power…

You might go on to argue that if it was not for the inherent conflict dynamics enacted at scale by stateness, (there was close to 60 state-based conflicts in 2023 alone), there would be no starting flag for races to the bottom, like nuclear weapon technology, in the first place. The collective “we” could not accomplish this at scale. Stateness, to some not so insignificant degree, is required. A utopian fantasy maybe but, in such a non-state based scenario, collective efforts into nuclear technology may shift toward renewable “clean” energy and interstellar travel. Not vaporising eachother.15

S.tech, hyper-connectivity and hyper-sociability all open different pathways allowing ordinary people to access information. Acting like artificial signals passing information across various local and global subspaces, what effect could the downstream second and third order effects, like increased sociability, have on collective stateness?

State-Based Anarchy

If you think I am being overly harsh towards stateness, and wanted academic support for such a critical take, look at the Realist counter to Democratic Peace Theory.16 The argument goes something like: all states behave in the same way (uncoordinated) because they want to preserve and expand their power base on the international stage, resulting, inevitably, in war (extreme lack of cohesion). This happens, the Realists claim, democracy or not.

Another Realist position, known as “Structural Realism”, is the position that the global system itself - essentially state-based anarchy - dictates the Game of Power and, because of this, states are forced into “survival mode” due to the structure of the GNUSS. With no centralised Orwelian Big Brother to enforce global interactions, tit for tat ensues. Only difference being that this game is played on the state level with nuclear brinkmanship and decentralised weapons technology.

Opposing a purely defensive motivation for such global conflict,17 “Offensive Realism” says that a state, as a geopolitical entity, looks for any opportunity to gain and expand power. When risk and reward lines up they go for it. The anarchic structure of the GNUSS compels states to prioritize self-help and security, leading to power competition. And war, at least minor conflict amongst territorial groups of apes, is more often than not the result. A grim number only bested by the Second World War, as 2024 came to a close 56 wars have raged just last year alone.

Sticking with the Realist position for a second, thinkers like Hans Morgenthau and Thucydides - considered “Human-Nature Realists” - proposed that states are drawn towards power because we, humans, are drawn towards it. Power dynamics are innate within human nature. Acting as a counterweight to the purely structural argument, what I find more interesting is that, just like technology, politics and society, it seems this position suggests stateness itself is an extension of us.18

If both humanity and states alike follow power laws, the question then becomes: what would happen if we could stop information from following power laws as well?

In Part 3 we will return to the structural layering world model introduced earlier, using it as a framework to guide a look into how s.tech interacts with and changes stateness. As the membrane between digital and physical dissolves ever further, entities within the global cause and effect chain - complex systems with the ability to influence global dynamics - stateness, sociability and technology - are all set on a collision course. The end games of which resulting in many drastic yet optimistic outcomes.

Rapid expansion and densification of links between entities (nodes) in a network defined hyper-connection. Whether those nodes are individuals, digital platforms, ecosystems, or other technological or natural systems, the different dynamics can lead to a higher or lower frequency and intensity of interactions between different systems and actors.

Hyper-connection involves the amplification of cause-and-effect chains across multiple layers of reality. From ecosystems and biological networks to human societies and digital infrastructure, events and actions in one domain increasingly trigger cascading effects in others, often in unpredictable and emergent ways. This complexity mirrors network theory, where dense interlinkages can lead to both systemic resilience and fragility, depending on how the network is structured.

Facilitating the rapid transmission of information and influence across diverse domains, hyper-connection shrinks temporal and spatial barriers between events and reactions. Accelerated by technological advancements like microprocessors, the internet, and AI, leading to real-time notifications across global systems, one result has been the blurring of boundaries between local and global, digital and physical, human and artificial.

Hyper-sociability describes a shift from traditional, localised social interactions to global, virtual communities facilitated by digital platforms such as TikTok, Instagram, and X/Twitter. Geographical and cultural boundaries dissolve, allowing individuals to connect, interact, and form relationships with diverse groups across the globe.

Unlike traditional sociability, which often depends on physical presence and occasional interactions, hyper-sociability enables frequent and near-instantaneous communication between individuals and groups. With a majority of the world’s total population using the internet daily, digital social platforms ensure that interactions are continuous and ubiquitous, creating a new norm for engagement.

Traditional physical gathering spaces like town halls or local meeting spots are being replaced by virtual environments where people gather, discuss, and collaborate. Social interactions are increasingly mediated by digital tools, redefining how communities form and how individuals participate in group activities, making the digital realm the primary venue for sociability.

Subspaces are adapted from the mathematical and classical physics concept of vector spaces, which are now being recruited as a tool for analysing geopolitics. “Subspaces” is also a nod towards new research into how “space” affects geopolitical dynamics.

See: Mitropolitski, 2011 for the use of Weber’s definition as an ethnographic tool. See: Wulf, 2007 for a counter to the Weberian definition and Lottholtz & Lemay-Hebert, 2016 for an re-reading of Weber with a focus on cultural and historical differences regarding legitimacy and how this influences the formation of social orders within a state.

For further ideas, see: Kampragkos, 2015, Suter, 2008 & Bloor, 2022

Under the GNUSS, some extreme scenarios (e.g. lack of state security regarding nuclear weapons technology) means such decay has the potential to affect upwards of billions.

See: Gerhard, 2002 for the mechanisms driving the fading of nation-states, Rotberg, 2003 for a look at how state failure, and failure of the GNUSS in general, lead sto local and global issues, Pauwelyn et al, 2014 for a look at the stagnation of forma international law, DeAngelis, 2018 for a look at the world beyond the state, Williams & McColluch, 2023 on “truth decay” and national security and Mathews, 2024 on how democracy isn’t declining, but the nation-state is.

Maybe I am giving us humans too much trust. But, being ultimately pro-human (which feels even crazy having to distinguish), we have the ability to flourish if a focus is turned towards solving collective issues and not creating them. Sometimes, when I look at myself in the mirror, I think: are we just inherently angry monkeys? Or can “we” transcend?

Which goes something like the more democratic states there are in the world the less conflict there is because democratic states are less likely to go to war with one another. This is because liberal democracies will tend to have similar value systems so they are more inclined to trust each other on an international stage. Intention is better understood.

As would be the case with “Defensive Realism”: states just want to maintain their power base and only expand when forced to do so (becoming defensive). If states want to expand power for power's sake the global system attempts to punish you.

That being said, the very act of being defensive denotes a threat. And really, state-level power requires equivalent state-level power to replace it.

This is an obvious point on the surface, but considering 38% of the global population live in Not Free Countries, many people around the world view their state as distinct to them, not as a direct extension of themselves.