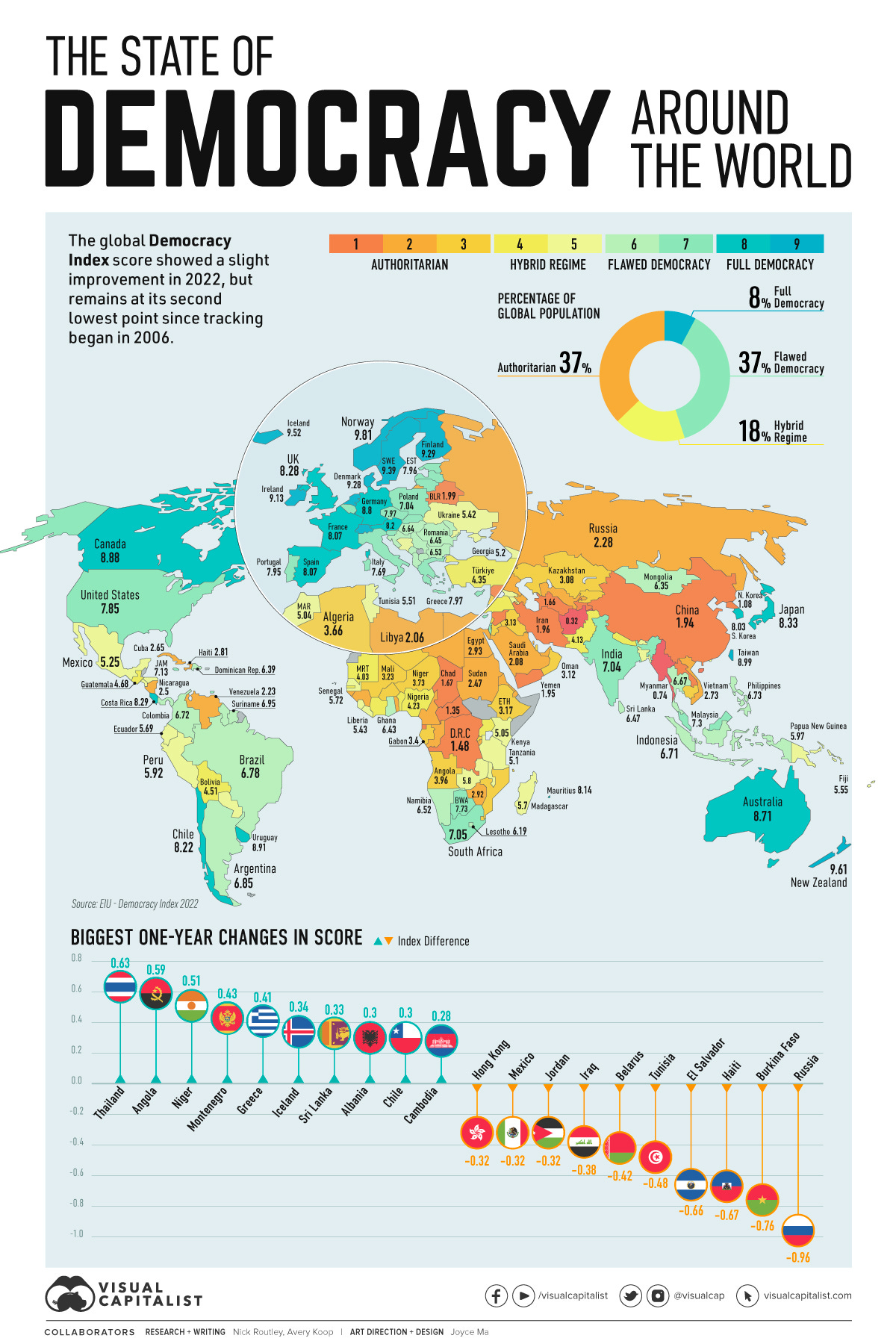

Democratic states around the world as per 2023 - note only 8% of the worlds population live in a state of “full democracy” (image courtesy of Visual Capitalist).

Structural S.Tech

Interconnection is at the core of society. That is why understanding hyper-connectivity (summarised previously as the expansion of the people-people links that comprise local and global social networks) is so important when looking at the potential effects that social technology (s.tech) can have not just on society, but stateness in general.1

In Part 2 we defined a global non-unified state system (GNUSS). Because the habitable space of our biosphere is demarcated into state-based subspaces,2 “stateness” is seen here as the most influential (or causal) dynamic engulfing geographical and societal subspaces. Seeing most of the geopolitical pushing and pulling originating from, and being governed by, this layer of subspace stateness, we can then imagine how cultural and societal pockets emerge within, and sometimes around, these spaces.

These pockets either remain somewhat “independent”3, or (more usually as history suggests) emergent complex organisations like religion, cultural movements, and leading historical figures, are bound inextricably to the state within closest proximity to them. Unless you are living completely “off-grid” chances are you exist within one degree of stateness or another.

In the previous article we also explored the “SLM Panarchy”. This panarcy-based “Structural Layer Model” can be used as a heuristic when thinking about societal and state-level organisation in a given area. The structure and function of the model acts like a “panarchy” - a conceptual model designed to look at how complex systems become “adaptive” over time. The SLM Panarchy suggests, then, until the space in question is completely void of subsystems (e.g. people, institutions), the triple-layered nest of components will continue to act in a recursive self-feedback-esque sort of way. Recursive patterns in self-organising systems and adaptive cycles in complex hierarchical structures bind the following three layers together: infrastructure, socialstructure and superstructure, and each can be used individually and collectively to explore the causal relationships “charging” the actions and behaviours of a given geographical space.

Keeping these state-based subspaces in mind, and thinking about how social organisations are structured from within these binds, and building on the framework developed in the GNUSS, we notice no definitively concrete boundaries demarcating each layer of the SLM Panarchy. The layers may instead be described as fluid, that is, they behave in a way akin to fluid dynamics. In a constant flux between turbulent and laminar, interacting with and influencing one another via the feed-back loops that criss-cross the entire panarchical structure, perhaps actions and causal chains like this may be why stateness is so pervasive.

Stateness is undeniably everywhere. All around each and everyone of us. (Even the tribespeople of North Sentinel Island still exist within the periphery of the Indian State; the uncontacted tribes of the Amazon still exist within the Brazilian, Peruvian, Columbian, Bolivian, Northern Paraguayan or Ecuadorian State.) So, given this, and bearing in mind the “non-unified” bit of the GNUSS, it becomes clear how thinking about hyper-connection might be fruitful with regard to understanding the relation s.tech has on such stateness writ large.

S.tech in the SLM Panarchy

But let us crop stateness out of the picture for a second. Taking the “social” from “s.tech”, having assigned the phenomenon of hyper-connectivity (something that could help us be closer to others e.g. peer-peer links) as a downstream effect of s.tech, we can see that component parts of the physical transport systems within the SLM Panarchy’s infrastructure (i.structure) layer - including roads, railways, airports, internet penetration and 5G networks - all directly impact this characteristic by increasing the other defining phenomenon downstream of s.tech: hyper-sociability (getting people from A to B, physically or digitally). In essence, systems within the i.structure layer increase interconnectedness, vis-à-vis hyper-connectivity, vis-à-vis hyper-sociability, in a given space.

Adding the “tech” to “s.tech”, our individual “tech stacks” - physical objects like smart phones, physical and digital networks like access to 5G and wifi - all help promote both the scope and the capacity for social media platforms. Further innovation occurs on both a local and global scale, enabling media sharing and a digital “presence” even in the farthest reaches of the world.

Sticking with the SLM Panarchy, when it comes to the “second layer” of social structure (s.structure) - any breaking of the agreement fields within a local area can be almost instantaneously shared across social media platforms. Outrage can be harnessed (justifiably or not) to promote collective action (e.g. mass petition signing or organised protests). The ability to record and share a person or entity breaking an agreement field is what binds s.tech to the s.structure layer, and again points to more illumination of the social space due to hyper-connectivity as a result of s.tech. Agreement fields, rather than stagnating into something not respected by the citizenry or the state alike, have the potential, through s.tech, to be reinforced in the best interests of the collection of people in a given area as a whole.

Back to stateness for a minute, any state-level injustices - injustices from the system that is supposed to be governing the subspace - can be brought to the surface (e.g. the Flint Michigan Water Crisis), exposed by grass root activism and amplified by social presences who hold the ability to share evidence and increase the public pressure on finding a solution by utilising s.tech as a primary method. S.tech’s hyper-connectivity becomes a spot-light for possible injustices.

That being said, because of the absolute power of the state (literally, by the Weberian definition, a collection of people who hold a monopoly of violence in a given area) this only works if the state in question allows such s.tech to be available in the first place. Some states (e.g. North Korea) do not allow social media posts at all, let alone posts with anonymity in le esprit de résistance. Whatsmore, even in states that pride themselves on freedom major s.tech platforms can be infiltrated and manipulated with false accounts, “bots” and hidden policies in order to sway the narrative and gain control over the information stream (e.g. the FBI’s and other US “intelligence agencies” involvement in the Twitter Files). States actively look to not only monitor but control the entirety of the s.tech structure, signifying the value of this technology.

Within the superstrucutre (sup.structure) layer, because frameworks have had more time to become calcified and rigid with age, s.tech is the least influential. Religious systems have had, in the case of Judaism for example, thousands of years to set themselves in place to the point that s.tech has little influence over how those religious bastions are positioned. Despite this, however, the characteristics of sharing ideas, abstractions and media has, and will always to some degree, influence individual interpretations of historical events, religious traditions and cultural beliefs. For example, s.tech used in a predominantly Christian locale may have different representations of the Jewish tradition than s.tech in a predominantly Jewish locale.

In this imaginary case, virtual assistants like Alexa or Google Assistant in predominantly Jewish regions may place emphasis upon the historical persecution of Jews by Christians, and Christmas and Easter might be discussed as cultural phenomena rather than religiously significant events, whereas in the Christian locale AI could frame Jewish holidays like Passover primarily in their relationship to Christian practices, such as the Last Supper or Easter, and there may be little emphasis on the diversity of Jewish practice, instead focusing on ancient temple traditions like Rabinnic Judaism. Through a process akin to an echo-chamber, or, in the spirit of religiosity, a “confirmation room”, already calcified beliefs can continue to be repeated and confirmed the more time you spend in a specific part of the digital town hall. Confirmations are for better and for worse.

But yes, s.tech can, under the right circumstances, disrupt even strict religious frameworks. Platforms like Instagram and YouTube have amplified progressive Christian voices, such as those of pro-LGBTQ+ pastors, challenging traditional religious frameworks on sexuality. Social movements like #ChurchToo (a branch of #MeToo) gained traction on social media, exposing sexual abuse scandals in religious institutions like the Catholic Church and Southern Baptist Convention. Barriers that once stone walled any scrutiny are now being eroded at an accelerating pace. Once again, the scattered yet strong beam of hyper-connectivity is illuminating a new digital landscape. S.tech is paradoxical: yes, in many ways social media platforms promote “fakeness”4, but in many others (and perhaps in more impactful ways), s.tech is a transparency maximiser.

Platforms like X/ Twitter have been used to share evidence, forcing religious leaders to confront systemic issues. Deconstructing authority, increasing visibility and amplifying generational shifts are, thus, all possible second and third order effects of s.tech coinhabiting the sup.structure of a state subspace. States take a majority influence over a spaces superstructure (e.g. religions and culture) yet, whilst s.tech struggles to shape the components of the sup.structure layer in a direct way as compared to stateness, it does seem to shape the interpretation of the layer by the people within it. In other words, s.tech influences the sensemaking of the people within a certain space, and that, when all is said and done, can count for a hell of a lot.

Clearly s.tech has found itself woven through the layers of global structure. As any weaver worth their salt knows, overlaps between layers are part of the process. The rise of tech giants like Meta/ Facebook challenges traditional state mechanisms and blurs the boundaries between the i.structure and sup.structure layers. Meta's ad platform, for example, is a critical tool for political campaigns, enabling micro-targeting based on user data. During the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election and other elections globally (e.g. Brazil, India), Meta was criticized for allowing the spread of misinformation and foreign interference (e.g. Russian troll farms). Certain key hubs for the development and distribution of s.tech sit liminally at a crucial point between state and citizenry.

Just look at how s.tech’s “global operations” often clash with national regulation; countries like India and Germany have tried to enforce content moderation laws, but Meta's policies and infrastructure often operate independently of state control. The blurring of structural layers within a subspace exposes, in some cases, the state’s limited control over digital infrastructure critical to democracy. As both a technological enabler and a cultural gatekeeper, Meta collapses the distinction between i.structure (foundational infrastructure like communication systems) and sup.structure (ideological apparatuses like media and cultural institutions). It is precisely because of this limited control over the digital space that states all look to control s.tech as much as possible.

Initial Weaknesses of S.tech

An arrow in s.tech’s side, global inequality means digital accessibility is uneven across regions, particularly in low-income or politically unstable countries. Barriers, economic or social, physical or digital, cause disruption. Like missing puzzle pieces, “infra-gaps”, quite literally holes in the i.structure layer where critical infrastructure should be, hinders the branching effect that s.tech can have on the s.structure.

Without effective i.structure in place, the sup.structures sphere of influence expands. In Sub-Saharan Africa internet penetration is approximately 35%. Compare this to over 90% in North America and Europe. Many rural areas lack the i.structure for reliable broadband or mobile networks, and with it, the hyper-connectivity that comes part and parcel.

Or take the civil war that has been raging between the military Junta state (dictatorship) and the people of Myanmar since 2021. Infrastructure was targeted in order to cut citizen communication (peer-peer links) enabled by s.tech. The video of the Burmese fitness influencer Hnin Wai dancing live on her social media whilst her cameras captured, behind and unbeknownst to her, the moment the military coupe began, speaks to the interaction between s.tech and state-level dynamics in a completely different but still very relevant (and oh so meaningfully ironic) manner.

With most of the country lacking electricity let alone internet connection, kinetic activity begins to take place in the sup.structure. With the most recent “ethnic cleansing” of the minority Rohingya muslim population, the Junta regime has weaponized one of the most fundamentally peaceful religions on Earth: Buddhism. Essentially, the military state has used the Rohingya people as a scapegoat for their own inadequacy. Capitalising on the infra-gaps, the Junta regime are a prime example of how a state can gain almost unfettered access to the sup.structure and, in doing so, manipulate majority sensemaking, moreover, decisionmaking, increasing ethno-religious tensions for their own purposes. S.tech can be weaponized. It just depends who is holding it, where it is pointing, and what the desired outcome is. Usually, if a state is wielding it, the desired outcome is control. Often, if private citizens are brandishing it, the warning shots are for change.

Compounded with high costs for devices and data, access to the digital space is even further limited. A basic smartphone, for instance, or a month worth of data, can cost a significant portion of an average income, making it an infeasible option for many.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the shift to online education exposed even more severe disparities. While students in wealthier countries could attend classes via Zoom or Google Classroom, millions of children in low-income regions were unable to participate due to lack of devices, internet, or even basic electricity. Infra-gaps thus pose a large problem, negating the potential benefits of s.tech in certain regions.

With all that being said, thinking about how social technology, and the downstream phenomena of hyper-connectivity and hyper-sociability, can come to influence the existence of states and thus the local and global levels of stateness in habitable subspaces around the world, is worth exploring next. Especially in the context of increasing democratic (or “effective”) governance.

Stateness = state-level organisation, both local and global.

See my note from Part 2.

e.g. stateless-nation

e.g. mis/disinformation, or actual fake social media posts, airbrushed and completely un-original.