Objects from Space, Minds from Machines: Living Systems from Artificial Worlds

The Expanse | Part 11

When boiled down, this series has been trying to make the following point:

It makes completely logical sense that living systems should emerge from the space of influence we call the technosphere.

Far from just supply chains, roads, cables, chips, software, data centres, everything we have built that forms an artificial environment, more specifically I am talking cyber space: that space we cannot physically touch, but the space where computational forms, programmes, active patterns, arguably cognitive functions within unique, complex structures all exist and, for all intents and purposes, appear to be rapidly developing in novel abundance, week in, week out.

But permit me to try and go back to first principles. For my own benefit more than yours. I am going to try and arrive back at this boiled down presumption by looking at the most basic building blocks of reality, starting with object creation within space.

First, let us set some axioms:

function implies form, and structure implies function.

In other words:

structure → function → form.

Equivalently, objects depend on shape, and space determines shape, so:

space → shape → object.

Together, I would say space provides structure, structure provides shape, shape provides function, function usually precedes form, and form is needed for an object to exist. That is:

space → structure → shape → function → form → object

or,

space constrains structure: structure shapes function: function gives rise to forms and objects.

Of course, this order is pretty much arbitrary. This is a heuristic, not a strict law. Unique only in so much as my mind rendered it so for the sake of expressing this article’s thesis. But it is backed by substantial, Lindy thinking. Plato, for example, who most have heard of in some capacity or another, viewed a first-principle space as containing “forms” which are enacted or instantiated into the physical space through active patterns, mathematical equations, embodied geometries. I imagine this as if pressing your face into a thin film of outstretched rubber: the imprint on the other side is simply a representation of the shape, texture, topology, geometry, of the form on the other side. True, in a modern scientific sense it would be more accurate to say space gives rise to fields (like the quantum field, the gravitational field, the electromagnetic field) and these fields then give rise to structure (like quantum fluctuations, curvatures, particles, large massed objects, and waves of energy). In fairness to this perspective, the use of “field” works well. It stands up both technically and metaphorically. One look at agricultural history suggests fields provide a structure for extended growth. Patterns of opportunity emerge from fields. But, starting with space and working our way up works for the thesis of this article, and so the general axioms are set, and we can continue on this brief cognitive excursion.

Philosophically, moreover, ontologically thinking about what constitutes the basic building blocks of reality, earlier in this series we thought about the tension between the belief that causal relations between structures create our reality: the lens of Ontic Structural Realism (OSR), and juxtaposed this to the opinion that objects themselves, the entire iceberg, are equally as fundamental to objective reality: the eye of Object-Oriented Ontology (OOO). Something like Gavin believing the iPhone is fundamentally real, whereas his best friend Smithy believes the supply chain, lineage of information and ideation, manufacturing and production line, and all the different points along a timeline of activity that constitutes the underlying fabric of the iPhone assembly itself is more real. One side sees objects, one side sees structure. In a nutshell: I don’t think it matters. Not because of some sixth sense “I see dead people”; because space seems to underpin everything. I have previously labelled this ontological perspective “spatial realism”. And, more importantly still, as far as we can observe, from space objects always assemble. If you consider quantum fluctuations objects in their own right, as kind of a hybrid quantum object realist framework, then objects exist as far as we can observe in both directions. As far as we can tell, a certain percentage of objects seem to consistently, over time, develop in such a way that they become “living”.

True, we only have our own biosphere as the prime sample pool. But let’s be honest: life probably exists everywhere in the universe. Whether or not you want to quote the Drake Equation, theories on planetary and cosmic speciation and evolution, astro and exobiology, or Fox Mulder when he exclaims “I want to believe”, as much as I love us I also believe humans ride both sides of special. On one side we no doubt are amazing creatures, because look at what we can do. In no uncertain terms, we seem to be able to perform magick. Innovative, loving, qualia-ridden beings inhabiting a rock hurtling round a big ball of plasma. Pretty cool. On the other hand we are just not that special, despite what our egos want us to believe, in the sense that there are probabilistically countless other intelligent forms of life not just in the universal expanse, but all around us within the confines of Earth. Biologically living systems assemble all around us in an animated dance of matter deriving its observable and physical form through fields like transcription and morphology, where the latter is the limits of possible configurations a system can arrange itself within: the shape of a system, and the former being the ability for structured information to replicate itself: DNA and RNA functioning as replicators and repairers to keep the system as close to a certain value as optimally possible. Through these processes it becomes tentative to imagine that systems exist all the way down, reinforcing themselves, or disappearing into an entropic wake, but still existing nonetheless.

What are systems but active patterns? Inputs, processes, outputs, loops and set values. In fact, one could argue that space itself has a pattern. That would suggest space itself is a system. Einstein’s General Relativity suggested space has a pattern to it: a curvature, and that it is curved through the geometry imposed by gravity, which incidentally requires an object, a collection of structure and systems, to exist. Large objects cause space and time to morph around them. The fact space can morph suggests a topology, and a topology suggests interrelations. Interrelations in-turn suggest structure. Quantum Field Theory suggests space is active and full of relations between subatomic particles, which are essentially constantly moving, what some describe as vibrating patterns of energy. This is not even a modern concept. Empty space, the Daoist traditions says, features functional value. Chapter 11 of the Dao De Jing makes clear that without the empty space of a home, you could not live in it, the space within the vase makes it functional. Whether or not the glass is half full or half empty is an irrelevant debate without the actual space to be filled. Could something that features functional value, even when empty, can be described as a system of some kind? When space is viewed this way, as some kind of system, it makes sense why we always see structure appear in our reality. Embodied pattern becomes structure and this allows systems to compound over time, to develop, to condense, to grow. By the time structure has developed into a whole object, the related set of systems has the potential to be quite complex. Richly layered, nuanced, highly interrelated to itself, its environment (space), and other systems and structure around it (objects). A springboard for activity.

A system is often classified as either being alive or inert, depending on a specific set of functions and subsequent features it expresses. Moreso, however, this classification is based on the processes contained within the systems architecture. When we think of “system architecture” one heuristic is assembly. How the various parts, components, and levels are integrated across scales, to form a fully functioning whole. So how can some assemblies lead to processes which can be correlated to our understanding of how some systems become “living”? Obviously, this can be quite a subjective classification, one imposed by a very biased observer: namely us, humans.

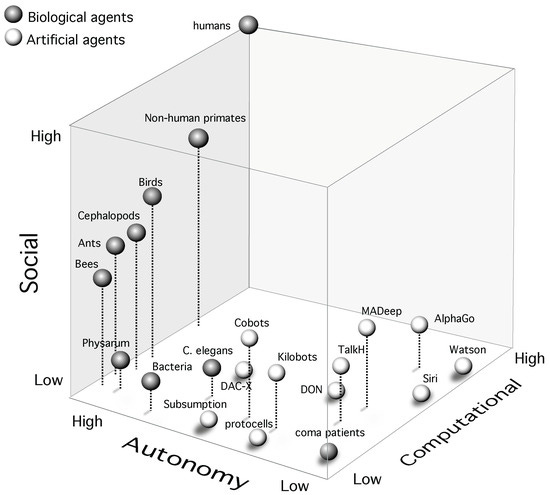

Oftentimes, and quite subconsciously, we become an “autobiographical observer”, one who superimposes itself onto the world around it, creating a mosaic of our own worlds, based on our individual and collective world views. The set of internal relationships within our system itself, the relationships to other living or inert systems, and our relationship to the local and global environments all play a role in this. René Descartes res extensa and res cognita - the physical material world around us, and the world models we all construct to get a grip on reality, the collection of minds, really should not be separate entities. As Dr. Levin points out in his “technological approach to minds everywhere” (TAME), abstract forms of minds seem to be everywhere in the physical and now technological world and whilst according to frontier research from Arsiwalla et al, “consciousness”, at least object assembly to the point of autonomy and high rates of social and computational complexity and depth, seem to be still only be within the realms of us humans, the latest agential AI systems do appear in the early stages of evolving characteristics like autonomy, and depending on which sources you place more confidence in, these artificial systems are becoming increasingly sociable, even using their own-brand, faster, more efficient language dubbed “gibberlink” to communicate specifically when an artificial agent engages with another artificial agent, AI-AI, all within the non-biological, non-physical, nor a strictly chemical cyber space.

“Morphospace of consciousness” - what a lovely model (Arsiwalla et al, 2022)

Whilst the qualia of consciousness is notoriously more difficult to pin-down than more general “minds” which are based more on cognitive, agential, and intelligence-based functions, I have previously labelled this set of relationships and the sphere of influence they inhabit “IOPEc space”: the subjective–relational world an agent inhabits, like a human’s experienced world of meanings, which derives itself from an interrelation between (i) interpretation, (ii) observation, (iii) participation, and (iv) experience. Somewhere deep in an object’s existence, the structural configuration has set in motion the eventual aliveness of a system, and such aliveness can be ascertained by the degree in which a system operates within its own IOPEc space. Not the system observing it, nor the system that has created it. The individual system itself. That is the trouble with minds: how do we recognise minds fundamentally different to our own? Morphology becomes a way of thinking about the structure, but it is not the structure itself. Just the same as Descartes “I think therefore I am” has become a metaphor for human reality, it is not the reality itself. Living systems think in their own unique ways. What are thoughts but patterns of cognition? Largely the ability to recognise patterns is determined by morphology, which is a downstream occurrence of structural change in space. The structure requires space, and once that space has been found, it determines the shape of said structure. Thus, understanding spaces remains fundamental when understanding objective structure, which is necessary when trying to understand everything else, including shape, function, forms, features, ultimately the whole object itself. When that object is a living system, clearly the idea that objects are inherently linked to spaces is important when we are thinking about spaces, as far as we can tell, that are “n of 1”. Our own technosphere is one of those spaces. As if setting up a demi-glace I am maintaining the heat and reducing this further still:

Because space generates structure and some structures become living and minded systems, and because humans have built a new structured space (the technosphere), it’s reasonable to expect life-like systems to emerge from our technologies.

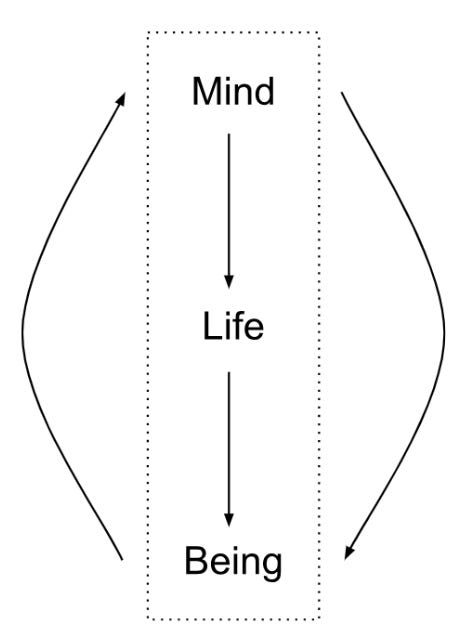

In many ways, “life” is quite subjective. Instead of thinking of systems in terms of being “alive”, it is becoming much more fruitful to think of systems in terms of “minds” and “being”. As brilliant thinker John Vervake puts it, “underneath mind is life and underneath life is being”. Visually, this stands:

When viewed like this, instead of narrowing collective efforts to unpick the phenomenon of life in the circumscribed centre of the spectrum alone it may be becoming obvious that good theorising (a process which has roots in what the Greeks called “theoria”, translating to a “meditation”) can be derived from spending time at the opposing poles of mind and being. Forgetting to traverse either end of the scale is perhaps why the ongoing “origin of life debate” has no end in sight: because those shouting are forgetting the essential interrelation life has to both mind and being. And when we think of mind and being we arrive back at structure and space. Patterns are inextricably linked to the mind. The mind is at once a collection of patterns, and a powerful pattern-recognition system. By seeing life as intertwined with mind, being, patterns in space, then developmental, evolutionary, physical, meta-physical, ontological, and cognitive questions flood in. The flow dampens the heat of debate and carries the conversation into new territory. Given both polar concepts are transjective, that is, neither being nor mind are subjective nor objective, but instead are based on a property of relatedness co-created by observer and world, then another implication becomes looking for life in spaces only recognised by us as featuring life is completely missing the mark. In fact, because humans are allopoietic systems, meaning we create systems other than ourselves, by the nature of our very being it becomes obvious that not only does space allow structure, but structure enables new space. Through our insatiable appetite for technology, by building, assembling, and forming relational structures, from wires and gears, minimotors to microprocessors and entire ethereally distributed global networks beckoning on Web 3.0, our version of life has created new space by developing our own extensions: new structure. Life, as we know it, is born in the physical. What this now means for life, coming out of a space we have created rather than co-inhabited, is a serious point worth paying attention to. I think Vervake put it best when he said “the processes of intelligence seem to participate in the same principles that produced the processes that produced intelligence”. Intelligence is a process that creates intelligence processes that create intelligence. It seems it is intelligence, not turtles, that go all the way down.

When thinking about life, mind and being are both interesting because both imply a self-organising quality. For something to “be” it must be organised in some coherent fashion. Equally, for something to have a mind its constituent parts must be organised in such a way that mind is able to be experienced through the strata of IOPEc space, even if the substrate itself is not directly responsible for the experience of mind. These distinctions quickly run into sticky ground when you include technology. Machines can be self-organising, and machines are not inherently alive, nor do they inherently feature a mind. What adds that extra sprinkle of aliveness to living systems? Processes like auto-catalysis, mentioned in the previous article alongside other functional processes like autopoiesis and allopoiesis, that is, the ability to create oneself and to create something other than oneself, are hallmarks of living systems. But do they constitute life itself? Hard to say. These processes are enacted through evolution. Evolution has provided living systems. Our biosphere is full of them. But evolution itself is not alive, is it? Metaphorically, we might think of evolution as a field rather than a process, in the same way General Relativity treats gravity as geometry rather than a force. A changing field rather than a specific process. Evolution certainly involves processes, it even evokes them, but evolution itself is a structure upon which other systems grow. Just like the Earth obeys the shape of gravity by following it around the Sun, living systems obey evolution by following the shape of it around the planetary space. Objects assemble from this space. Living objects included. To understand object evolution more generally we should think about how other complex objects, aside from biological life, are formed.

A tool that we have been returning to throughout the previous ten parts of this series is Assembly Theory (AT), because for me it acts like Occam’s Razor and cuts through a lot of unwanted fat to get right at the heart of the issue: object assembly in space over time. In the previous article AT was applied to living systems, namely us humans, to look at the individual parts in an exercise of mentally assembling the various parts of a complex, living system. What if the loose framework of AT’s assembly index is applied to complex objects originating from the technosphere? How would this match up? What insights could be transferred from one space to another?

Technology is an augmentation of reality. Tools, human-level artefacts, are used to augment individual and social practices. Writing implements changed the way we communicated. Axes changed the way we changed the environment around us. Technologies then became a way of applying complex knowledge to problems, becoming itself embedded within artefacts requiring engineering. Mobile phones changed communication as much as steam engines morphed transportation. Then ecologies of technology started to grow. Sets of technology symbolically related to. Co-evolving functional nested units, light bulbs, power stations, hard drives and broadband. Ecologies supporting growth, of more technologies, more artefacts. Overlapping and interrelating to amass delicate yet dense layers of infrastructure, multiple levels of technological ecologies, interconnected to form basic societal coordination, transforming transportation, communication into global supply chains and networks. As time moves on, technological epochs take shape. Durations of time witness sets of infrastructure supporting social systems, like the industrial age blending into the millennial World Wide Web (WWW). All of these changes, co-evolutions, assemblages, taking place within the technosphere. A space propped up by the structures assembled by us. We come from space, and create structures to create more space.

What can be expected to come from that new space? That Expanse.