(This article has been taken from my original article, released in the Ancient Origins Magazine in 2020 under the title Sri Lanka: Impressions on the Island of Ancient Secrets. Since updated, revised and re-released.)

What Do We Know?

My entire body was jerked to one side. The aeroplane banked hard to the left as the pilot prepared for landing. A vibrant-green landmass took up the entire view through my cabin window. It was early 2019, and the sight of boundless canopies dropping into deep, rolling valleys made me conscious of how little I actually knew about the real Sri Lanka thousands of feet below.

Located approximately 1,400 kilometres east of the southernmost tip of India, with a landmass of 64,740 km² (that is slightly smaller than Scotland in the UK), the one thing I had not comprehended was the scale of countless tragedies this compact tropical paradise had bore witness to in recent times. A sporadic civil war, which sparked in 1983 due to a flashpoint in political tensions, had stayed ignited until the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam forces were finally stopped by government troops in 2009. In 2004 the Boxing Day Tsunami ravaged the island, claiming the lives of over 35,000 people. More contempoary, the appauling 2019 Easter Sunday suicide bombings throughout the island caused mass devastaton and unrest. These are terrible, unforgettable events and should no doubt be treated as such. They have left the people and the land scarred. But Sri Lanka is much more than tragedy. It is home to rich and vibrant cultures. Some of the kindest people you could ever meet. And, through a little digging, it soon becomes clear that the island houses a far more rich, far more enigmatic history than we have been led to believe. Could these clues, left dormant on this largely unknown island, help us to unravel our own forgotten ancient past?

Shrouds of Mystery

There was not much history written about Sri Lanka before the Common Era. Written records were unfavoured. Instead oral traditions were the chosen method of transmitting events, knowledge and accounts of the foundation myths from across the island. This should not deter you from lifting up the rock and seeing what you can find for yourself. The bountiful island has some significant prehistoric sites, albeit often nestled away, far beyond the well-worn paths and bustling beach-side resorts that get snapped up and regurgitated on social media.

Fa Hien cave (also known as Pahiyangala cave) is found deep in the densely packed rainforest that grows throughout the western Kalutara province. It is known through radio-carbon testing to have been inhabited for at least 28,000 years (Kennedy, K, 1989, P. 384).

Similarly, in Batadombalena cave located within the unforgiving mountain-ranges that traverse the Sudagala region, and in Belilena Cave situated within Kitulgala - the wettest region on the island - some of our oldest anatomically correct skeletal remains are found. Known as “Balangoda Man” (or homo sapiens balangodensis), these fragments were unearthed by archaeologists between the 1960’s and 1970’s. They were dated to the Upper Pleistocene - an epoch broadly ranging from 129,000-11,700 years before present (YBP) (Kennedy, K, 1987).

Whilst undoubtedly there has been human settlement in Sri Lanka for tens, maybe even hundreds of thousands of years, despite this, so few (close to none at all) written records, even for the past thousand or so years, exist to this day. This makes tracking the history of the Island of the Sleeping Lion difficult to say the least.

The view of the surrounding terrain in the western Kalutara province, where the Fa Hien cave is situated and the earliest remnants of human survived, maybe even thrived, in prehistoric Sri Lanka. (Taken from WikiCommons)

Instead, what we know about ancient human existence in Sri Lanka appears simply through the testing of skeletal remains such as those found in the aforementioned caves, or through the discovery of stone tools, dug up and given a date based on the stratigraphic layer they were found. This is then used to extrapolate estimations for when human activity began, and when more complex social forms began to flourish on the island.

How do these tests take place? How accurate are they? Tests are conducted using radio-carbon dating. Archaeologists remove small pieces of organic material from a site, subject it to a mass spectrometer, a device capable of counting the carbon-14 atoms present in the material. When compared to baseline data this process provides a ball-park age for the tested material and, by association, the age of the site in general where the given material was found (American Chemical Society, 2016). While favoured as an accurate method for many decades, Sturt Manning, a Professor of Archaeology at Cornell University, believes that factors like the fluctuating carbon-cycle may affect the results and “potentially undermine several current archaeological and historical positions and controversies” (Manning et al, 2018). Although Manning was referencing his work in the Southern Levant Region, not Sri Lanka, Dr. Alan Zindler, a Professor of Geology working out of Columbia University, goes further and notes that “carbon dating is unreliable for objects older than 30,000 years” (Browne, M. 1990), suggesting Manning’s criticism may hereto apply to almost every pre-Upper-Pleistocene site that has been radio-carbon dated. That is exactly the period attributed to the Balangoda Man. The foundations for what we know about our early Sri Lankan ancestors are built on loose grounds.

Radio-carbon dating can provide a solid basis when determining estimations for objects belonging to a more recent time, however cracks creep into these foundations the further back into our ancient past we push. We must always be aware of the possibility that these sites and their dated remains, here on the island of Sri Lanka, may be shrouded in even more mystery than we are first led to believe.

Lord of the Jungle

Aside from my dim headlights and a few pricks of remaining starlight it was pitch black. Zooming down a narrow, too-often-times treacherous Sri Lankan road, apart from the pot-holes to keep us company it was empty, not a soul in sight. The welcoming roadside residents of Sigiriya village seemed to be all sound asleep. As they should - it was not even 04:45 in the morning. Despite this ridiculous hour, I had risen to the croaking of the frogs, wiped the sleep from my eyes and was currently giving my best effort not to end up headfirst into one of the countless ditches littering the path. It would be fair to ask what we were doing. We were looking for a certain large rock to climb up, in the hopes of observing a giant, sleeping lion.

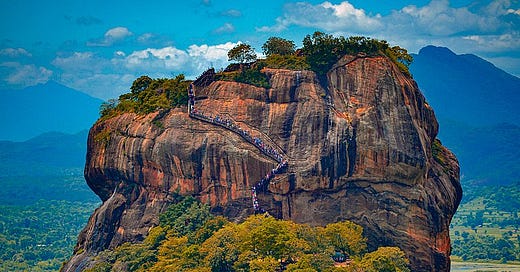

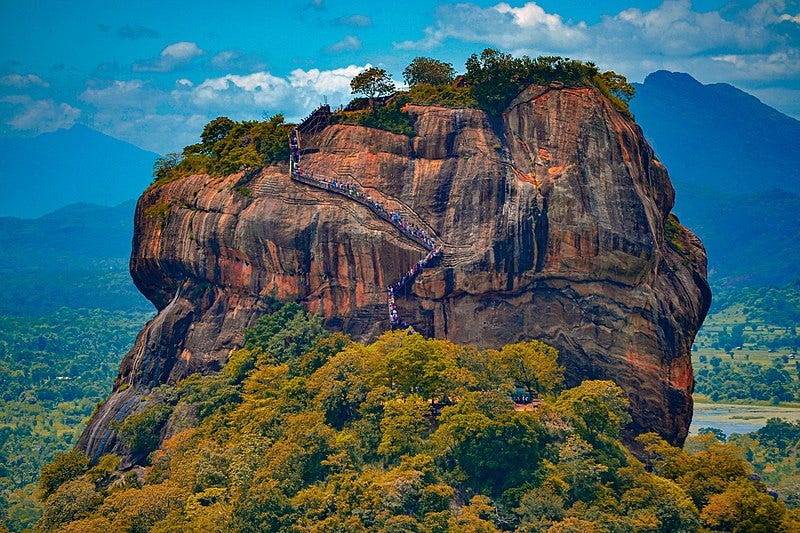

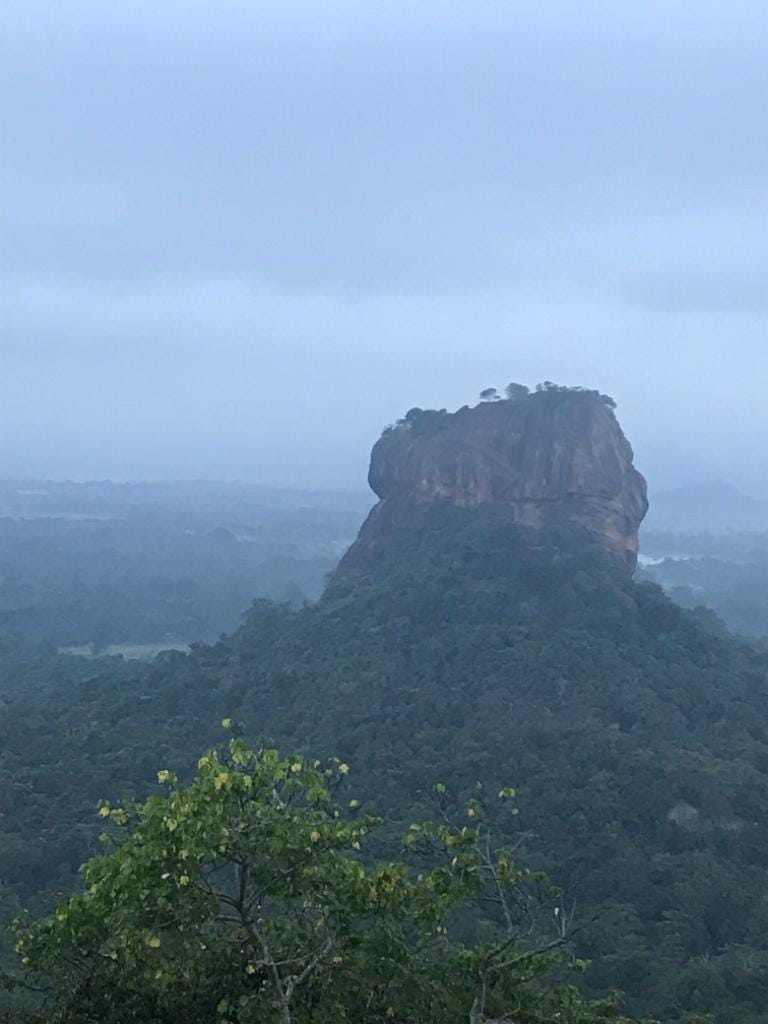

About an hour or so later, with an electrified atmosphere, we were, along with maybe twenty others, gathered on the towering rock-summit. Silence spread, all mutually respecting the eerie, palpable energy emanating from the scene unfolding before us. We were perched, somewhat precariously, 200 metres up above sea-level on a granite inselberg known as Pidurangala Rock. Mountainous though motionless, the “lion” that we were observing was the neighbouring Sigiriya Rock. Granted the status of a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1982, we were all gathered to watch the “suryoday” (Sanskrit for “sunrise”) over the enchanting “eighth wonder of the world”.

As the sun began to finally break through the cloud cover, I took note of how it suspended motionless in the sky for a few spectacular moments, almost seeming to deliberately linger atop Sigiriya’s lion rock. This was interesting for a few reasons. First off, the view was absolutely breathtaking - an added bonus and the reason why we had spent the last half an hour breathlessly clambering up Pidurangala’s mini-mountain summit in pitch darkness.

Our view over the adjacent Sigiriya; the sun broke through the clouds moments later... (Photo courtesy of F. Burnand).

Secondly, the fact that I had been re-reading at the time a book authored by Graham Hancock and Robert Buaval, the concept of a sky-ground connection was fresh in my mind. Both authors focus on the alignment of certain ancient monuments in Egypt with the sun and other celestial objects (like various star systems) at certain times of the year. As I was standing on the neighbouring summit, observing the sun now slowly rise over Sigiriya, the words of Hancock and Buval echoed in my mind, and a theory, admittedly a very rough one, began to form. As above, so below.

King, Not Creator

With around 14.7 million visitors each year, it is safe to say that the Giza Plateau is moulded into the very fringe-come-beating-heart of the Egyptian city. A bustling hub of tourist activity, Giza’s surrounding plains not only hold the three immense pyramids, but the enigmatic and imposing feline guardian, the Great Sphinx.

Whilst attracting only a few thousand tourists each year, the Sri Lankan counterpart, Sigiriya (“Lion”) Rock pawls in comparison to the Egyptian feline. In some regards this is a good thing. Less exposure means less chance of damage by over-activity, preserving as much of the original material as possible whilst allowing visitors the chance to still see it up-close and personal. An obvious downside however is less tourism - the less revenue, the less chance there is for future funding for innovative (and much needed) future research.

Approaching Sigiriya Rock later in the day, working my way through the complex of pristine-crafted gardens and selfie-sticks that surround the giant citadel. (Photo courtesy of F. Burnand).

Supposedly, the Great Sphinx of Giza was created over 4,500 years ago under the Egyptian Pharaoh Khafre (Tiakkanen, 2017). This has long since been disputed by independent researchers like Schwaller de Lubicz (1989), John A. West (2012), Graham Hancock alongside Robert Bauval (1997) and Robert Schoch (2017) who site a number of reasons, including water-erosion in the Sphinx enclosure and astronomical alignments to the constellation Leo. Whatever the case, all believe the great lion was constructed in an older age than the consensus dating today. Could this research be used as a framework for an investigation into Sigiriya?

The “Culavamsa”, a historical record of Sri Lanka dating back to the fourth-century BC, first records Sigiriya’s initial occupation. Looking at the translation - as the original is written in “Pali”, a language apparently chosen to record the teachings of Buddha in ancient Sri Lanka (Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2019) - the start of Chapter 39 tells us how King Kashyapa I of Anuradhapura (not to be confused with the Vedic sage of the same name), killed his father during a political coup and was forced to flee, proceeding to build his palace and battlements atop Sigiriya. We are led to believe this was a very deliberate choice as Sigiriya was a place famed to be “difficult of ascent for human beings” (Wilhelm, 1929, P. 42). It is not hard to understand why human ascension is so difficult: the hardened magma formation soars vertically, standing at its pinnacle over 200 metres (650 feet) from the densely vegetated floor. Slick with moisture and risk almost all year round, it is no wonder Kashyapa fled to this natural, impregnable fortress.

A frontal view of Sigiriya’s “lion” staircase. Evidently all that remains of the supposed staircase are the two frontal paws, along with the assumption that a great feline head was also once in place, slotted grandly above them. Where or what happened to this giant head is still an unsolved mystery. (Taken from WikiCommons - top & WikiCommons - bottom).

A frontal view of the Great Sphinx of Giza. Notice the extreme weathering on the body and enclosure walls that initially led researchers to question its assumed age and Khafre’s true involvement in its construction. (Taken from WikiCommons).

A feline paw emerges from the sand. (Taken from WikiCommons).

Upon arrival, it is assumed Kashyapa began constructing a fortress-come-pleasure-palace, aimed to defend against any retaliation from his disposed brother, Moggallana, the rightful heir to the Anuradhapurian throne, whilst of course, living the high life as King in the meantime. This appeared to have been completed with lightning-speed, but this speed would be all the more explainable if there was already remnants of an existing structure on the citadel summit.

Extracts from the Culavamsa, a mere few sentences, are some of the only ancient source-codes connecting Kashyapa to Sigiriya. If you have been up there, atop the sleeping lion, it is hard to imagine the place was constructed for the simple sake of a renegade king’s home. An energy resides there. An energy so alike other ancient sites, ranging from Peru to Egypt to Mexico, one that is hard to ignore. If there was something there before the Kashyapa takeover, as I mentioned earlier there is not much “official” history at all when it comes to ancient Sri Lanka left to record it. There is, however, ancient myth.

Structural Myth

Since the works of the 20th-century mythologist Joseph Cambpell, along with the paradigm-shifting analysis by academics Giorgio de Santillana and Hertha von Dechend (1969), it has become widely known that myth is not simply fantastical tales conjured up by ancient, overactive imaginations. It is instead a powerful and rather significant part of real human history.

I like to think of the structure of myth as a water-droplet. If I have just watched Marley and Me, a tear-drop. This droplet shape has three interrelated yet distinct layers. The first outermost layer of myth is the surface level. This is the narrative - the story - that makes transmitting the myth across time easy. This is the most relatable part and the most entertaining. Next we have the middle layer. This is the part of the narrative that requires a bit more digging, a bit more thought-processing. This is the vein of analogy, the pulse of metaphor, that studied-readers will be able to tap into, to feel, if they pay enough attention. Then we are left with the final layer. Here we have an inner bead of pure wisdom. This bead is the real reason the founders of the myth transmitted it in the first place. Narratives were woven with parables and wrapped in humour or tragedy for the soul purpose of this beads survival through the ages. Obscure, it is often hidden deep beneath a thick crust of abstract meaning. To access this dense nucleus requires multiple threads of tacit knowledge and lots of digging. But once reached, it is the most fruitful part of the myth and the part that most people tend to miss.

What tends to be found across global foundation myths is that this bead, this inner sanctum of structural myth, has many similarities no matter which culture nor from which time the myth originates. Whether cosmological in origin, or a record of a prior cataclysmic event, this pearl shines for anyone to hold their breath and take the plunge. If there were in fact great civilizations flourishing in Sri Lanka before the time of Kashyapa, capable of creating marvels like the Sigiriya Complex, would they have in some way featured the same foundation myths as other civilizations, whose own genesis are now also being brought into question?

One key recurring theme throughout world myth is that of a great flood. Discussing exactly this in his collective work “Underworld”, Hancock notes how the “Rajavali”, part of the “Ceylonese chronicles based on archaic oral sources” describes how large parts of Sri Lanka were once destroyed by massive flooding, where large cities, settlements and over “twenty miles of the coast, extending inland [were] washed away” (Hancock, 2003, P. 248). We only have to think back to the 2004 tragedy to get a sense of how destructive the forces of water can be on the island.

Whilst many would (and have) dismissed this as mere fantasy Hancock, as he so often does, pushed on. He discovered “that a large tract of land would indeed have been exposed between Tuticorin [India] and Mannar [North Sri Lanka] – just as the chronicle said – at around 16,000 years ago”, positing that “Sri Lanka was indeed much larger than it is today with the greatest extent of antediluvian [pre-flood] land... exactly where, ‘in a former age’” a giant citadel once stood (Hancock, 2003, P. 248). Ergo, ancient, lost and wholly unknown civilizations may have once spread out over Sri Lanka, spanning from the Indian subcontinent, evidence of which lay somewhere below the murky waters.

It begins to seem far more likely that Kashyapa, after committing the act of patricide, seeking an immediate safe-haven, fled to Sigiriya, a place where an already-existing, prehistoric, and easily defendable outcrop lay ready for the newly disposed king to put his vast resources to work. From archaeological records we know that the area immediately surrounding the Sigiriya Complex has been inhabited since the third-millennium BC (Cooray, 2012, P.41). This gives ample time for a proper settlement to be established long before Kashyapa appeared on the scene. Given what we already know about our ancient ancestors’ long-held lineage on the island, and the fact that foundation myths speak of a former age where much of the land was washed away by a giant flood, could the bead of wisdom present in this myth point to a storied history, much more complex than mere underhanded kingship?

What is more, a 2002 study into the irrigation systems surrounding Sigiriya, attributed to Kashyapa, concluded how the “basin was quickly abandoned” and “never in use for any appreciable length of time” (Risberg, Myrdal-Runebjer, Miller, 2002, Pp. 27, 41). Whilst not only highlighting the small length of time Kashyapa was present at the site, this begs the question, could he really have gone to all of the extreme lengths now evident in order to create the features of the complex citadel in this small window of time?

Maybe, just like the Egyptian Pharaoh Khafre who many believe has been miscredited for the creation of the Sphinx, Kashyapa simply “re-inherited” Sigiriya for his own purposes, stamped his name on it, wrote himself into the annals of history yet was not in fact the original architect of the enigmatic settlement. Whilst we are working with limited resources, another branch of possibility could lead to further clarity: does Sigiriya’s sky-ground connection point to more clues in order to unravel this knotted past?

Cover Image: The terrain covering Sri Lanka is breathtaking in its scale and wonder. (Photo taken from: WikiCommons)

References

American Chemical Society. 2016. Discovery of Radiocarbon Dating in National Historic Chemical Landmarks. (Accessed: http://www.acs.org/content/acs/en/education/whatischemistry/landmarks/radiocarbon-dating.html)

Browne, M. W. May 1, 1990. Errors Are Feared In Carbon Dating in The New York Times (online). (Accessed: https://www.nytimes.com/1990/05/31/us/errors-are-feared-in-carbon-dating.html)

Cooray, N. 2012. The Sigiriya Royal Gardens: Analysis of the Landscape Architectonic Composition. TU Delft: Netherlands. (ISBN: 148003097X, 9781480030978).

Hancock, G. 2015. Magicians of the Gods. United Kingdom: Coronet.

Hancock, G. 2003. Underworld: The Mysterious Origins of Civilization.

Manning, S. W. et al. June 2018. Fluctuating radiocarbon offsets observed in the southern Levant and implications for archaeological chronology debates in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115 (24) 6141-6146; DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1719420115 (Accessed: https://www.pnas.org/content/115/24/6141)

Katupotha, Jinadasa & Kodituwakku, Kusumsiri. (2014). Diversity of vegetation types of the Pidurangala Granitic Inselberg, near Sigiriya, Sri Lanka: a Preliminary Study. 10.13140/RG.2.1.2564.4006. (Accessed: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/277140686_Diversity_of_vegetation_types_of_the_Pidurangala_Granitic_Inselberg_near_Sigiriya_Sri_Lanka_a_Preliminary_Study)

Rich, J. C. 1988. The Materials and Methods of Sculpture. (ISBN: 0486257428, 9780486257426)

Sparavigna, A. C. 2013. The Solar Orientation of the Lion Rock Complex in Sri Lanka in The International Journal of Sciences. 2. 60-62. 10.18483/ijSci.335. (Accessed: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/259289258_The_Solar_Orientation_of_the_Lion_Rock_Complex_in_Sri_Lanka)

La Paz, L. 1949. Azimuth determinations in meteorites by means of time readings in Science, 110, 438. (Accessed: http://articles.adsabs.harvard.edu/cgi-bin/nph-iarticle_query?1949PA.....57..513L&defaultprint=YES&filetype=.pdf)

Walton, D. 22 April, 2017. Who Built the Fascinating Ñaupa Iglesia? Mysterious Ruins in the Sacred Valley of Peru in Ancient Origins (online). (Accessed: https://www.ancient-origins.net/ancient-places-americas/who-built-fascinating-aupa-iglesia-mysterious-ruins-sacred-valley-peru-021345)

Wilhelm, G. 1929. The Culavamsa I. Oxford University Press. (Accessed: https://archive.org/details/TheCulavamsaI/page/n3/mode/2up)

Kennedy, K. A. R. & Deraniyagala, S. U.1989 Fossil Remains of 28,000-Year-Old Hominids from Sri Lanka in Current Anthropology. 30:3, Pp. 394-399. (Accessed: https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/203757?mobileUi=0&)

Kennedy, K. A. R., Deraniyagala, S. U., Roertgen, W. J., Chiment, J., & Disotell, T. 1987. Upper pleistocene fossil hominids from Sri Lanka in American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 72(4), 441-461. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.1330720405 (Accessed: https://nyuscholars.nyu.edu/en/publications/upper-pleistocene-fossil-hominids-from-sri-lanka)

Tikkanen, A. December 28, 2017. Great Sphinx of Giza in Encyclopædia Britannica, inc (online). (Accessed: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Great-Sphinx)

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. March 28, 2019. Pali Language in Encyclopædia Britannica, inc (online). (Accessed: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Pali-language)

Karunathilaka, P. V. B. 1991. Metals and metal use in ancient Sri Lanka in Sri Lanka Journal of Humanities. Vol. XVII & XVIII (1991 - 1992). 104-118. (Accessed: http://dlib.pdn.ac.lk/handle/123456789/2224)

Risberg, J. Myrdal-Runebjer, E. Miller, U. 2002. Sediment and soil characteristics and an evaluation of their applicability to the irrigation history in Sigiriya, Sri Lanka in Journal of Nordic Archaeological Science, (13), 27–42. (Accessed: http://www.archaeology.su.se/polopoly_fs/1.166286.1392035742!/menu/standard/file/J13_risbergetal2.pdf)